The innovation sweet spot sits at the center of desirability, feasibility, and viability, the three tenets of design thinking as defined by esteemed design firm IDEO. Customers want my product. My company can deliver the product. The product provides sustainable value to my business. Chances are, as problem solvers, strategic thinkers, or product leaders, we may already be familiar with design thinking and the importance of evaluating every product idea against these three tenets prior to investing the organization’s time and money.

Unfortunately, in our haste to deliver a new product against a deadline, our excitement to bring an idea to market, or under pressure from management, we don’t always do the proper due diligence. In fact, we often cut corners, sometimes unnoticed. But each time we fail to fully vet a new idea, the chances of successfully launching a product that is both adopted by customers and drives growth decreases. Additionally, the risk of failure increases, whether it’s a failure to launch, missed customer expectations and limited adoption, financial loss, unrealized market potential, unscalable or unsupportable solutions, or misalignment to the organization’s strategic objectives.

In the following three articles, we will provide fact-based methods to evaluate ideas for their desirability, feasibility, and viability to help you mitigate risk, recognize bias, and gather the right data to make informed decisions successfully bringing products to market.

Four pitfalls to avoid when

assessing a product’s desirability.

Desirability

Does Our Product Meet a Customer Need?

Desirability is the first factor to consider when vetting a new product idea, as the ultimate purpose of a product should be to satisfy a customer need. Simply put, a desirable product meets a customer need and solves a customer problem. And without some assurance that a customer will actually buy your product, it’s difficult to ensure a potential return on investment for your company. Validating a product’s desirability reduces the risk of failure and lowers the cost of launch and adoption.

Many organizations rush to be first to market or to quickly match a competitor. But without knowing whether a product idea meets a customer’s needs, the chances of failure increase. Google+ is a great example. In the rush to compete in the social media space, Google didn’t truly understand their customer needs or that those needs could be met through differentiating features. Had they taken the time to properly evaluate the desirability of Google+, they could potentially have prevented the product’s ultimate demise. Project managers use commonly practiced methods to capture customer feedback and validate desirability, e.g., voice of the customer analysis, surveys, or journey mapping, and this article will explain how project managers can avoid common mistakes made during that validation process.

Pitfall 1:

Assuming the idea is the solution

Think back to the latest discovery or current state discussion with your customers in user interviews, focus groups, or casual check-ins. Was more time spent listening and probing, or solutioning and describing the benefits of a hypothetical product (the BIG idea)? If it included more of the latter, the feedback gathered may be biased and may not reflect the true problem your customer needs solved. To determine if an idea is truly desirable, you must understand the current state of what the customer is experiencing and the true problem to be solved. By assuming the idea is already the solution, you assume you already understand the problem. When you sell your idea and solutioning how your idea solves the first “problem” you hear, the conversation becomes focused on validating your own idea rather than validating the problem to be solved. Even if you do understand the problem and the idea is the solution, give yourself a chance by listening before selling or solutioning. It is understandable to be excited about your new product idea. It is also understandable to feel the pressure to “close the sale” and get buy-in, either to gain approval from executives or for personal gain and career advancement. Selling before listening usually validates assumptions already made based on our own emotions and motivations.

As you conduct your next round of customer interviews, surveys, or focus groups, consider these suggestions to prevent personal views and assumptions from biasing the conversation.

1. Do not mention the idea. As soon as someone mentions an idea, the conversation becomes about the idea, not the customer. Focus instead on gathering facts about what the customer does and feels while performing a task, the challenges they experience, and the needs they have.

2. Avoid hypothetical behaviors and problems. As problem solvers, we love to generate solutions and design the ideal product and the ideal future state. But the future state is hypothetical. It is an informed guess at best and shouldn’t be the basis for desirability. The current state is factual and provides the richest insight into the actual problem, and it should determine if the idea addresses the problem and would be desired.

3. Avoid questions that include would, could, or should. These conditionals yield opinions rather than facts. When a customer mentions a problem, ask, “What did you do when … ?” instead of “What would you do if … ?” The former yields a factual response about the current state. The latter assumes a solution that has been projected onto the customer.

The basis of desirability is authentic customer insights. While these simple steps can help mitigate your bias and natural tendencies to uncover these insights, it’s critical to also consider the bias and tendencies of the customer. They can lead to another common mistake.

Pitfall 2:

Assuming the customer is telling the whole truth

A customer’s world is the set of activities they perform. Problems they experience while doing those activities are certainly impactful and can be a hinderance to their daily routine. However, it’s common for the customer’s most recent problems to be top of mind in an interview or survey with a product team, even if they are not really the biggest problems. Customers tend to unintentionally overestimate the impact, frequency, and severity of their most recent problems. If not recognized, this selection bias, or frequency illusion, may lead to the validation of an idea aimed at mitigating a problem with minimal negative consequences, limited frequency, or cheaper workarounds.

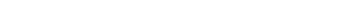

When assessing the desirability of an idea through conversations with the customer, get the customer to tell a story to paint the complete picture of the tasks surrounding a problem. Ask “Tell me” and “Show me” questions; for example, “Tell me about a time when … ” or “Show me how you use … ”. Both questions let the customer tell a story. Ask qualifying questions to better understand the severity and frequency of the problem as well as the customer’s current solutions to address the problem. Dive deeper at specific moments in their story that catch your attention to tie emotion to a problem — “How did you feel when … ?”. Then probe for details — “Why?”, “Why did you do you do that?” The mistake is not diving deeper than the story and accepting the customer’s initial response as the whole truth.

Notice that all the above questions are neutral and do not lead the customer to a particular response. By answering these questions, the customer will begin to break down the problem themselves to help uncover the root to assess desirability against. Mitigate bias that can appear in the conversation by asking these questions from a neutral perspective.

If possible, observe the customer performing the tasks when the problem arises to identify discrepancies between what the customer says and does. Observation puts you in the customer’s shoes to better develop empathy, giving you more context to probe and get past any surface-level answers. Additionally, data gathered from observation is more quantitative and a valuable supplement to the more qualitative data gathered solely from conversations.

Pitfall 3:

Assuming the end user is also the buyer and supporter

Consider this scenario: Your Product organization has an idea for a groundbreaking timekeeping software tool. It has automatic time entry based on configurable task tagging and calendar appointments. Based on early estimates, the idea could improve the efficiency of time entry by over 50 percent. The users your team consulted loved the idea. However, the idea flopped when it was presented to their managers and the IT leaders who approve the purchase of software. Users loved the efficiencies gained, but the manager (the buyer) wanted a more robust reporting capability. At the same time, the IT leader (the supporter) wasn’t keen on the effort required to create and maintain the metadata behind the task-tagging feature.

As product leaders, we often put ourselves only in the shoes of the end user and forget the needs of the buyer, who must often consult with technical and operational experts before making the purchase. For that reason, the desirability of a product must be validated against the needs and problems of users and the buyers and supporters of the product.

If the idea is undesirable to all three personas, the product will likely never make it into the hands of the user. In some cases — primarily B2C products like the Amazon Kindle — the user, buyer, and supporter may be the same. In other cases — most often B2B products like timekeeping software — the user, buyer, and operator are different.

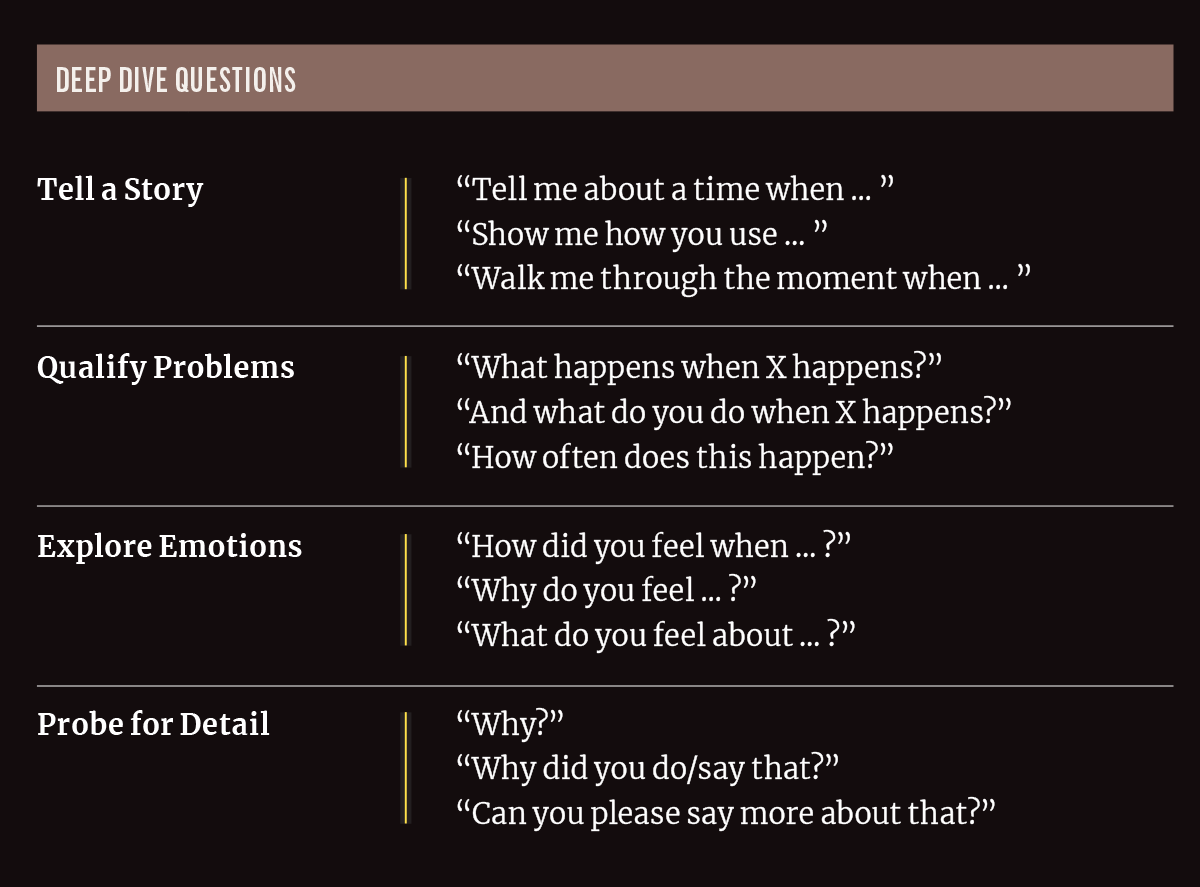

In order to ensure a product is desirable and addresses the unique problems of each persona involved in the product’s life cycle, from purchase to maintenance, it’s important to first identify the key stakeholders

Start by conducting a stakeholder mapping exercise that places the end user at the center. Ask yourself:

Who else would need to use the product, and how are they related to the end user?

If not the user, who would purchase my product?

If not the user, who would support the product after it is purchased?

Next, organize the resources identified into personas, creating new personas for those with different needs, desires, motivators, etc. Data gathered for each persona, including segment size, price sensitivity, and adoption habits, will help inform viability decisions down the line.

Finally, create journeys for each persona based on observations and conversations. Identify problems to be solved and potential desirability overlaps across personas. Identify success measures at each touch point in the journey as a reference point for desirability; for example, minimize the time it takes to complete a timesheet.

Pitfall 4:

Assuming customer problems don’t change

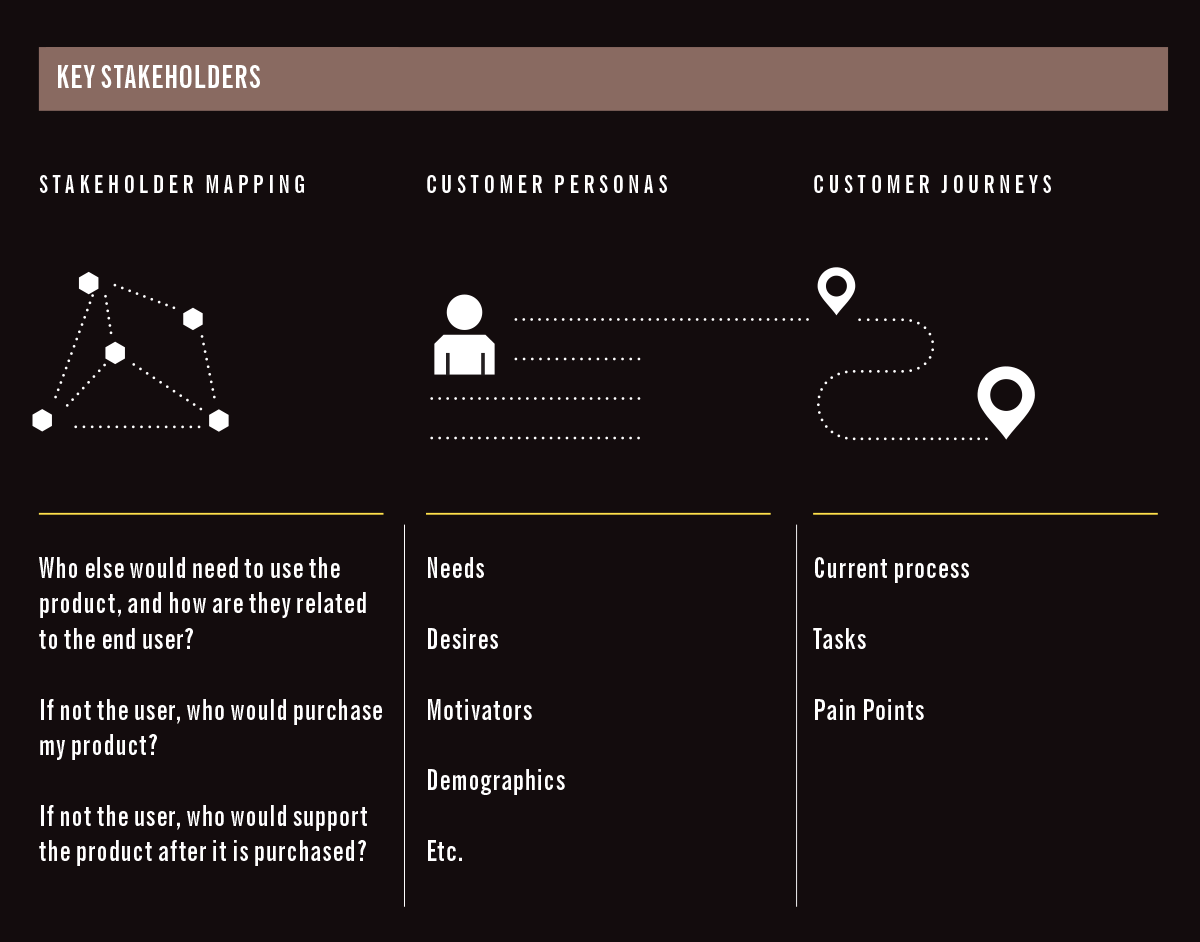

Customer needs are not static and are constantly evolving. As customers’ needs change, the ideas and products that address them must also change. In a previous article, “Product Management: Drive Customer Centricity Across the Organization,” we stressed the importance of establishing feedback loops and maintaining organization alignment to customer needs. Here are a few ideas from that article to help prepare your organization for a more regular evaluation of desirability against current customer needs and incorporate changes into idea and product refinement.

1. Establish feedback loops. Feedback loops should be in place at strategic points in the journey for each customer persona. Gather both qualitative and quantitative data through focus groups, customer interviews, and direct observation as well as more light-touch mechanisms such as voluntary response outreach campaigns and rapid surveys. Leverage third-party tools if budget allows to track usage, usability, and feature adoption of existing products. Establish a process to manage feedback, prioritize changes, and close the loop with customer outreach.

2. Position product teams to gather feedback directly from customers, both formally in scheduled cadences and informally at casual check-ins. Feedback gathered through sales, SMEs, relationship managers, or customer support is valuable, but as a product leader, firsthand observation is preferred for the reasons discussed above. Product teams who rely only on indirect feedback received via “middlepersons” may find that ideas or product enhancements based on that feedback may only address the problem presented by the messenger and may not have wider adoption.

3. Incentivize a culture of continuous improvement, where needs and problems are continuously reassessed. Establish customer cadence expectations to track that product teams are talking regularly with customers. For existing products, track feature adoption over feature deployments to prioritize alignment to needs over quantity and speed. Track feature change requests and support tickets whose themes may indicate a misunderstanding of customer needs or desirability of a particular feature.

These activities will help establish a continuous flow of customer insights to allow the product organization to evaluate desirability and implement feedback against real-time customer needs. Measuring desirability should never stop. It is a continuous process to evolve ideas and inform feasibility and desirability assessments. Despite an abundance of data, companies can still miss insights and build products that customers don’t adopt (Google+), flop after launch (Quibi), or fail to reach the launch pad. As humans, we naturally seek the path of least resistance to solve problems. When we’re determining the desirability of an idea or product during the customer and market research stage, the shortcuts we take can be driven by our own assumptions and underlying bias, which, in turn, impacts the true desirability of our ideas.

Avoid hypotheticals and conditionals to reduce your own personal bias in customer conversations.

Identify the true problem to be solved through observation, evoking emotions, and probing for detail to mitigate any recency bias.

Develop customer personas for users, buyers, and supporters to understand the desirability of an idea against the problems of each stakeholder.

Establish feedback loops internally and externally to continuously incorporate customer feedback into product ideas and improvements.

Doing so will help the product organization better understand the true desirability of an idea before assessing its feasibility and viability.

Three pitfalls to avoid when

bringing a new product to market.

Feasibility

Can Innovation Meet Practicality?

No matter how innovative the idea, not every product makes it to market. Just because a product is desirable, meets a demand, or solves a problem for which customers are willing to pay does not mean that the product is feasible. As any shrewd executive understands, for a product to be successful, a company must have, at minimum, the capabilities to develop the product, bring it to market, and continue to deliver on its value.

As product teams discover the wants and needs of their customers and generate product concepts accordingly, they must also evaluate whether delivering the product is realistic for their specific organization. No company has unlimited time and resources, and product leaders must eventually make a judgment call about the feasibility of a new idea. Problems arise, however, when leaders base their decisions entirely on the technical feasibility of the product while overlooking the organizational, operational, and cultural factors that must also that influence a company’s ability to implement the product idea successfully.

Leaders cannot make decisions to invest both time and dollars into a product haphazardly and without due diligence. Leaders should only give the green light after a holistic understanding and evaluation of what the organization needs to put in place across the full life cycle of the product, from strategy to launch to ongoing maintenance.

This article outlines three pitfalls that regularly derail product leaders when assessing product feasibility and provides the critical questions executives need to ask to avoid them.

Pitfall 1:

Not evaluating feasibility early enough to kill bad ideas fast

It’s a great moment when a team finally finds a product idea that solves a tough customer problem. The team has gathered feedback about the idea and the evidence is clear — customers want the product. What could go wrong? Unfortunately, a lot can go wrong. A common mistake occurs when teams run with the product idea — generating excitement in the organization, creating buy-in, and even investing in design — but fail to evaluate the critical question of feasibility in parallel. Teams need a comprehensive view of the organizational, operational, and technical capabilities that must come together to design, build, pilot, operationalize, and sustain the product in the long term. This information is critical to have early on because it informs whether bringing the product to market is even possible within their specific company. The sooner teams conduct this analysis, the faster they can kill off bad ideas. As hard as it might be to accept, learning early that a seemingly great idea is not feasible can prevent the loss of time, money, and talent later.

In some organizations, leaders may feel compelled to push a yet-to-be proved feasible product idea forward based solely on market or investor desirability. John Carreyrou’s book, “Bad Blood: Secret and Lies in a Silicon Valley Start Up,” highlights an extreme example of this type of thinking, in which the top leadership at Theranos continued to seek investment and put extreme pressure on its scientists and engineers to develop solutions that were not possible at the time. In the end, the continued investment in a technology that did not work as advertised led to loss of over $600 million1 in investments and criminal charges being pressed against founder Elizabeth Holmes and top executive Ramesh Balwani.2

As organizations often learn (the hard way), the more they invest in a product, the harder it is to kill off that bad idea, forfeit its sunk costs, and pivot to a more feasible concept. Instead, when teams discover a solution that they believe customers will desire, there should be immediate follow-up around the idea of feasibility and viability. Thinking about feasibility, desirability, and viability at the beginning of a project will help teams develop a comprehensive and balanced approach should they decide to invest in the product or solution.

Pitfall 2:

Focusing on a too narrow definition of feasibility

One of the biggest mistakes a team can make when evaluating a product’s feasibility is failing to enlist a broad enough coalition of stakeholders to evaluate its ability to succeed. In engineering-driven product development, this mistake is especially prevalent. These companies are prone to focus on whether a product can be successfully built, while ignoring the organization’s ability to market, sell, and support the product.

A product management team with mature launch practices will instinctively enlist the input of sales and marketing to answer several questions, including: Are there nontechnical requirements that must be met for customers to accept a product? Does the company have the ability to take a developed product to market and generate sustainable demand? Are there windows of opportunity in the market that we must hit for the product to succeed? Do we need to develop new marketing or sales capabilities to launch the product successfully?

Similarly, the seasoned product team will also collaborate with operations to address the following questions: Do existing teams possess the skills necessary to support the product? Can we hire additional personnel to meet growing resource demands? What new processes and support models do we need to establish to ensure customer success with the new product?

A great case study of a company focusing on a too narrow definition of feasibility involves Motorola in the late 1990s. Already established as one of the world’s premier handset makers, Motorola launched the ambitious Iridium mobile phone product line that customers could use anywhere on the planet via a network of the company’s geosynchronous satellites. While Motorola’s R&D teams created a great technical marvel with the handsets, company executives failed to consider the handsets’ feasibility from a market and operations perspective. The product worked exactly as designed at launch; however, the engineering team missed numerous customer requirements that were imperative for market success. Namely, customers deemed the handsets too large, clunky, and expensive.

Had Motorola R&D spent more time with its marketing and operations teams, they may have recognized earlier in the process that the bar for feasibility was much higher than anticipated. Engineering would have understood that not only must the technical aspects work but that the product had to meet market needs in terms of size and cost. For Motorola, delivering the handsets in a smaller form with lower material costs was not technically feasible at that time. Meanwhile, Motorola’s primary rival Nokia focused on developing cheaper, smaller, low-power digital devices customers found much more appealing and overtook the market as terrestrial cell networks became more ubiquitous in urban areas. Motorola never recovered from its product mistake and was soon eclipsed by other telecom leaders, including Nokia and Blackberry. Had Motorola looked beyond their narrow definition of feasibility, they might have pursued a different product strategy that allowed them to retain market leadership and fend off competitive threats.

Pitfall 3:

Weak governance hinders new product development

If a company possesses the technological capabilities to build a product, as well as the sales, marketing, and operational capabilities to bring the product to market, many leaders think they’ve checked the box on feasibility. However, these same leaders often overlook the critical organizational constraints that can derail the development and launch of the product. In addition to tapping stakeholders across the organization for input when evaluating new ideas, leaders must also consider how organizational structure, governance, and decision-making norms impact their company’s ability to build, launch, and operate a new product. A failure to understand the impacts of these organizational ways of working can lead to missed market opportunities and revenue.

For example, without strong governance, the structural separation between product teams and the delivery teams who are charged with development can derail product development. We have seen cases in which product teams have confirmed a clear customer need and made a strong business case for a new product. However, when the team tries to put the product into development, it is met with impediments. Sometimes, the delivery team may not have sufficient resources to dedicate to the new product, and the company’s funding model does not empower the delivery team to reallocate resources. Other times, the delivery team may determine that the priorities from another part of the business are more critical. Without clear governance, this type of separation can lead several challenges:

1. Inefficiency From Undefined Product Delivery Processes: Organizations without strong governance often lack established mechanisms to deliver a new product. Defined processes and interactions include the expected contributions, deliverables, and information from various teams to inform decisions across the product life cycle. For example, where does handoff between the product teams and delivery teams begin and end? If there is not a clear agreement of what activities and documentation the product team will accomplish before engineering teams begin design work, the organization can find itself at an impasse, further delaying the schedule. Establishing customary processes and interactions will help to clarify accountabilities and responsibilities to maintain progress.

2. Delay From Escalated Decisions: When product and delivery teams do not have a framework to guide decisions and prioritization at each level in the organization, teams often escalate product decisions — sometimes to the highest level of the company — for a final answer. A chain of escalations leads to unnecessary steps, a loss of time and resources, and leaders not empowered to drive action. Escalations can also result in a senior leader making the decision without understanding the full context of the trade-offs and implications. Instead, establishing a clear model for how teams negotiate and prioritize work and the scope of decision-making at all levels can enable companies to better flex and adapt to changing customer demands and bring products to market faster.

3. Missed Allocation of Resources: Without strong governance for prioritization and subsequent resource allocation, leaders may unwittingly fund and staff products that do not actually align to their company’s strategic priorities. Consider this example: A company is undergoing a digital transformation and has an API-first strategy, yet a legacy product continues to generate significant but flat revenue. Instead of reallocating talent and funding to focus on the growth opportunity of building APIs, the legacy product leader makes the decision to continue fully funding the legacy product. This decision makes it nearly impossible to meet the stated objectives. Product governance should ensure connection between the company’s strategic objectives, product prioritization, and resources allocation. While this idea is simple in concept, organizational complexity can prevent this critical alignment.

Establishing a clear model for how teams negotiate and prioritize work and the scope of decision-making at all levels can enable companies to better flex and adapt to changing customer demands and bring products to market faster.

The challenges above highlight the importance of leaders setting a strong governance that defines process and interactions to deliver a new product, accountability for determining product prioritization, and how leaders allocate resources to support prioritized products. Establishing this type of governance model can improve collaboration across functions and make new product opportunities more feasible to achieve.

Assessing the feasibility for a new product launch is a critical step in the product development process, and one that is rife with pitfalls. To avoid the hidden traps that cost companies valuable time and resources, product leaders must put on their risk management hats, build broad coalitions of stakeholders, and answer the difficult questions that determine whether a product should move forward. This evaluation needs to start early in the process and continue iteratively throughout the gestation life cycle of a new product. Effective executives from across functions should aim to clear roadblocks. No product launch goes exactly as planned, but leaders who understand the pitfalls and stay vigilant through the process stand the best chance to reach market with a desirable, feasible, and viable product.

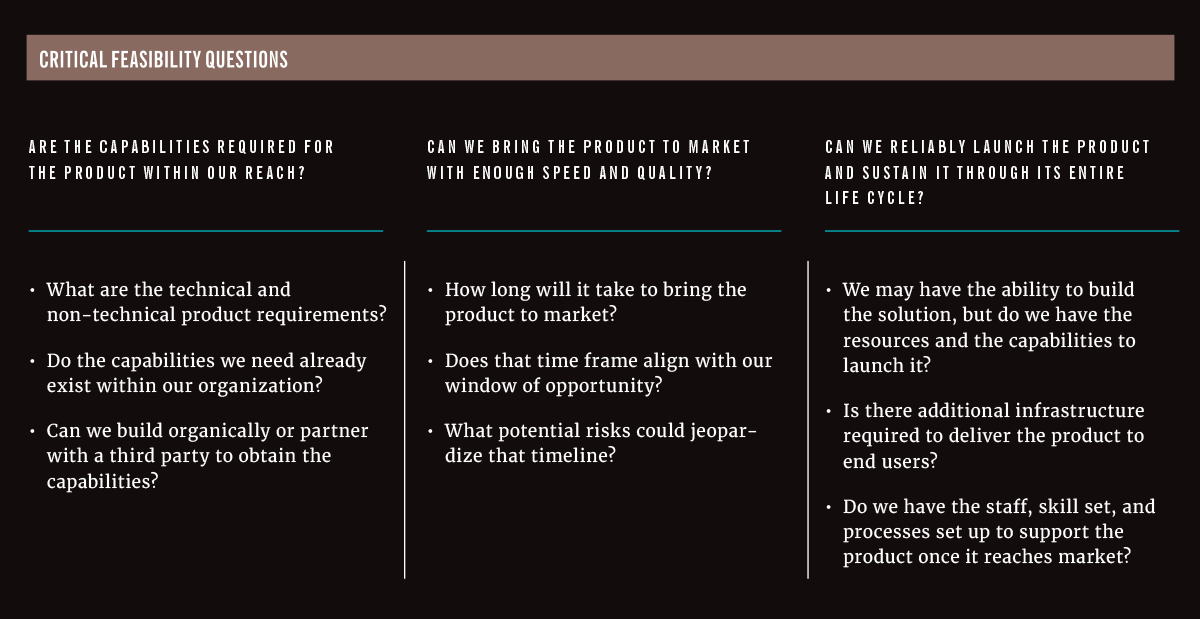

The chart above outlines the critical questions a leader must ask across an organization — from product, technology, operations and HR to finance, sales, and marketing — to make an effective feasibility decision.

Three pitfalls to avoid when assessing

a product idea’s viability and how to avoid them.

Viability

Will It Make Us Money?

When developing a new product idea, it is critical to assess three key factors: 1) the market’s appetite for the product – Desirability; 2) the firm’s ability to deliver the product – Feasibility; and 3) whether the product will generate sustainable value for the business — or the product’s Viability. In addition to a product’s desirability and feasibility, product leaders must understand if and how their product will add value to the company.

To put the significance of understanding product viability into context, think about Alphabet Inc. Before Alphabet Inc., Google, LLC housed multiple subsidiaries on its profit/loss sheets right along with its online advertising and search engine businesses. These subsidiaries were mostly smaller firms producing cutting-edge, generation-redefining technology products. Many of the subsidiaries were not financially viable even though their products addressed customer problems in innovative new ways (Desirable) and the companies had the capability to deliver them (Feasible). At the time, the leaders at Google Inc. were willing to expose their established businesses to potentially unviable products, but their shareholders were not. Separating Google, LLC from its edgier subsidiaries made it easier to kill off those deemed unviable while protecting the stable revenue generated from their core advertising and search businesses. This was the entire point behind creating Alphabet Inc.

Assessing viability is the key to turning an exciting new customer-oriented innovation into a sustainably profitable product line. Said another way, viability is the difference between “Question Marks” and “Stars” in the Growth-Share Matrix. The process of determining a product idea’s viability is also the product’s business case and serves as the first financial gatekeeper before major investment — in essence, ensuring good money isn’t thrown at a bad idea. Skipping this step often leads to overspending on product development, launching a product at an unsustainable price, and/or negative impact to your company’s brand. By the time business leaders realize the impact of failing to assess their idea’s viability, it’s often too late. They’re stuck deciding whether to invest more to potentially salvage the idea or simply walk away from sunk costs.

But what are the steps to successfully assess the viability of a new product idea? And what are some common pitfalls when assessing a product idea’s viability? Good news! Here are three common pitfalls business leaders face when assessing product viability and ways to avoid them.

Pitfall 1:

Assessing the viability of a product idea too late

It may come as a surprise, but a product idea’s viability is often not confirmed until after the product has been developed. “How could that happen?” It happens all the time right in front of our eyes. A firm will sink millions into research and development for a new product. Then they’ll conduct a pilot, beta testing, or small market test with real consumers. The firm will then designate the product as viable or unviable based on the success or failure of the pilot. Granted, this approach will prove/disprove a product idea’s viability, but it’s pricy and frankly, a poor allocation of resources.

Product viability should be assessed as part of a comprehensive product development strategy. The best time to execute a viability assessment is after confirming the product idea’s desirability and feasibility, but before finalizing the business objectives and goals for the product.

Why this order of operations? Simple. Many of the outputs uncovered when confirming the product idea’s desirability and feasibility are essential to the viability assessment. For example, the two most critical outputs determined from confirming product desirability are the target consumer and product feature set. Specifically, understanding the segment size, preferred price point, product feature needs, and adoption habits per target customer persona are instrumental in estimating the product’s potential revenue. Similarly, the most critical feasibility outputs that feed into the viability assessment are understanding the operational and technical capabilities needed to build, launch, deliver, and support the product in the market — all of which drive the viability assessment’s cost estimate. Finalizing the business objectives and goals follows the assessment because it’s simply a waste of time and effort for a product that isn’t viable.

Pitfall 2:

Choosing the wrong type of assessment

It’s important to understand that there are multiple ways to assess the viability of a product idea. Each way requires a different level of investment and yields different results. Choosing the right assessment type depends on where the product is in its life cycle as well as the firm’s current environment (rapid growth, capex reduction, financial volatility, etc.). Choosing the wrong assessment type often leads to the negative impacts mentioned near the start of this article (e.g., overspending on development, unsustainable pricing, negative brand impact).

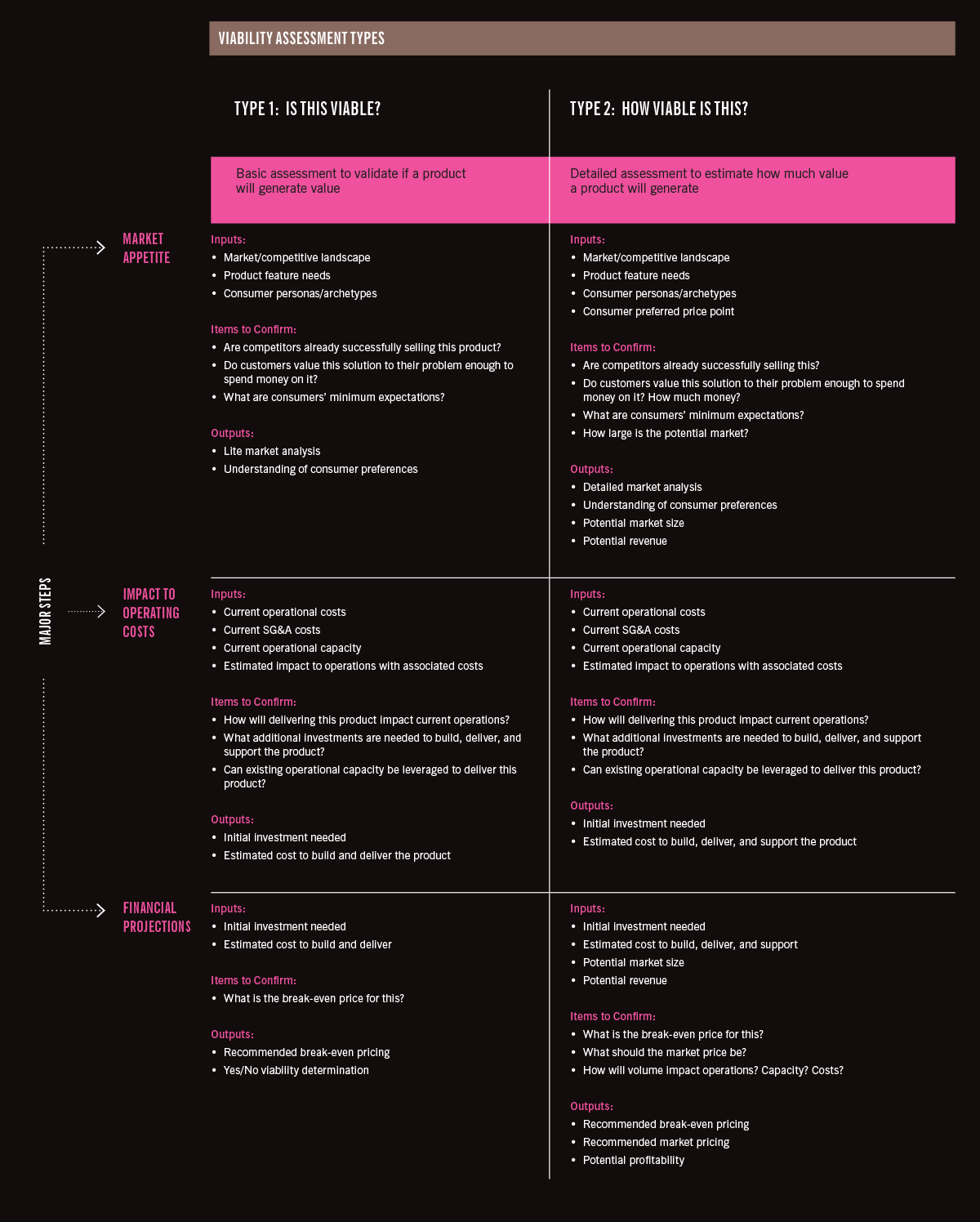

For this article, we’ll assume the assessment is taking place during product strategy development, long before the actual product has been made. The question here is “How should I conduct a viability assessment for my idea?” Before this question can be addressed, it’s key to understand what answer is desired at the end of the assessment. There are two ways to assess viability during strategy development, and each yields a different outcome.

The first way is a basic assessment that confirms whether the product has the potential to be viable. The output of this assessment type is typically a simple, “Yes, this has the potential to be viable,” or “No, this does not have the potential to be viable in its current design.”

A “Yes” output from this assessment type — let’s call it the “Is this viable?” assessment — should not be taken as a green light to pursue product development. Rather, it should be viewed as a thumbs-up to continue researching and developing the business case. The main benefit of “Is this viable?” is simplicity and speed, as it can be executed by one person in a few weeks with minimal capital investment.

The second assessment type — let’s call it “How viable is this?” — is an expanded version of the first assessment that estimates the potential financial impact of the product. Essentially, this is the business case for the product, and the output is typically a prediction of how much value the product will add to the business (profit, revenue, cost savings, etc.). The main benefit to this assessment type lies in its detail. The investment needed is higher, but the outputs are more comprehensive and lead smoothly into product planning. That said, remember that both assessment types are cheaper than a failed product launch.

Interestingly, the major components of each assessment type are the same and involve confirming: 1) the market’s appetite for the product; 2) the impact to operations from delivering the product; and 3) the financial projections. It bears mentioning that these components align nicely with the profit equation (Profit=Revenue-Cost) and the standard structure for building a business case. This is not an accident. Estimating potential profitability is the most common method for assessing financial viability.

Pitfall 3:

Not planning for next steps, whether the idea is or isn’t viable

Regardless of the assessment type used, the outputs should indicate whether the product idea is worth pursuing or should be reevaluated. How the outputs are used, however, varies based on assessment type and the specific results themselves. Either way, it is critical to plan a path forward for the product idea after assessing its viability. If not, a potentially profitable game-changing product idea could lose steam and sit on a shelf while the entire firm rapidly declines around it. If this scenario seems far-fetched, never forget that Kodak developed the technology for digital photography long before their competition … and their bankruptcy.

Here’s a breakdown of next steps by assessment type and results:

Isn’t Viable

Obviously, not all product ideas are viable, so it’s important to prepare for an unfavorable assessment. First, don’t get emotional. Realizing the product idea is not viable can be tough, especially after confirming both its desirability and feasibility. And while emotional investment in the idea may already be high, it’s important to keep a level head and understand that the idea is not dead in the water. Rather, this is an opportunity to analyze the product idea and redesign it to cross the viability threshold.

Second, it’s important to understand why the product was deemed unviable. Some questions to consider are: Were some of the parts too expensive to manufacture? Could the product’s design be tweaked to make it cheaper to produce or deliver to market? Can the product become viable through purchase or partnership? Or was the product’s unviable determination due to unfavorable market conditions? Is the market size too small or experiencing a negative swing that impacts your target segment? Other factors, like a lack of infrastructure needed to deliver the product, could also negatively impact the product’s viability determination.

Remember, an unviable determination should not halt all work on the idea. Instead, use it as an opportunity to further analyze the idea and identify ways to improve it. Never be afraid to go back to the drawing board or patiently hold an idea until market conditions are more favorable. And, most importantly, don’t give up.

Is Viable

Again, in the “Is this viable?” approach, a “Yes, this has the potential to be viable” output does not mean the product idea is fully vetted, only that it has potential and warrants further investment. That further investment should involve completing the more detailed assessment.

It’s fair to ask, “If the basic assessment just leads to the more detailed assessment, why not jump straight to the more detailed assessment?” The answer is simple: The more detailed assessment requires more work, time, effort, and resources. Often, this level of investment is reserved for high-priority initiatives backed by the firm’s senior leadership. The basic assessment is better for newer product ideas or pet projects that do not have adequate funding. In fact, the outputs of the basic assessment often become the pitch to senior leadership for the funding to complete the more detailed assessment. Also, executing the more detailed assessment involves completing the same steps included the basic assessment. Delineating between the two and reviewing after the basic assessment is the first complete review of the product idea (Desirability + Feasibility + Viability) before major investment.

If the results of the more detailed assessment (“How viable is this?”) reveal the product idea is viable, the next steps follow the product management process and include defining the critical product planning elements. First, define the business goals for the product and confirm that they align to the firm’s overall objectives. This will help ensure the new product compliments the existing product/portfolio mix. Assuming the product idea has been greenlit by this point, the next step is to begin detailing product use cases and customer journeys. Here, it will be important to define the product’s maturity stages, including Minimum Viable Product (MVP), and align the product’s feature set to the stages. This will help prioritize work efforts and reduce time and investment needed to take the initial version of the product to market.

Confirming the viability of a product idea often coincides with the end of the discovery process transitioning into product planning and development. It’s the foundation upon which many other strategic and operational decisions will be made. Knowing that, it’s easier to see why ensuring product viability is confirmed in a timely and comprehensive manner is so important. Remember that it’s also important to reconfirm viability as product design, build, and launch decisions are made. Often, the product that is eventually launched is not the same one that passed the viability assessment. After launch, this kind of viability analysis may have a different name, like “benefits realization” or “performance management.” In the end, it’s all about making sure the time, effort, and resources put into a product idea are worthwhile investments for the firm.