Can I play too? How the integration of professional sports championed diversity

Nelson Mandela once said: “Sport has the power to change the world. It has the power to inspire. It has the power to unite people in a way that little else does. It speaks to youth in a language they understand. Sport can create hope where once there was only despair. It is more powerful than government in breaking down racial barriers. It laughs in the face of all kinds of discrimination.”1

Mandela’s words align with the history of integration in the United States. Against the social norms of the times, a handful of forward-thinking coaches, administrators, players, and owners in major league sports tested the common sports adage that winning transcends all. Over several decades, the opportunities these individuals created have translated to significant commercial success for the sports industry. They also provided global exposure for athletes of all backgrounds, races, abilities, genders, sexual orientations, and gender identities to challenge discrimination and break down stereotypes while driving worldwide economic growth.

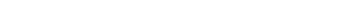

Before school integration, lunch-counter protests, and bus boycotts, major league sports teams added African-American players to their ranks. Kenny Washington reintegrated the NFL in 1946. Jackie Robinson broke the color barrier in major league baseball in 1947. Chuck Cooper was the first African-American player drafted by an NBA team (the Boston Celtics) in 1950. And Althea Gibson was the first African American to compete at Wimbledon in 1951.2 While there were other players of color in U.S. professional sports before this integration, they fell victim to colorism, and players in professional sports could not appear to have any African heritage.3 Following Jackie Robinson, Cuban, Puerto Rican, and Dominican athletes integrated individual teams. Orestes “Minnie” Miñoso integrated the Chicago White Sox in 1951 and Carlos Paula integrated the Washington Senators in 1954; both men were Cuban American.4

Inclusion in sports timeline (non-exhaustive)

Sources: Bold Business, Baseball Almanac, Bleacher Report, The Undefeated, Black Soccer Membership Association, Blackpast, Briana Scurry, NBA, CNN Money, CBS News, La Vida Baseball, International Paralympic Committee. *WUSA is the precursor to the National Women’s Soccer League.

Many early pioneers of professional sports integration used their platforms to encourage social change. Some worked with the NAACP and other social justice organizations geared toward racial equality,5 while others used their platforms to protest discrimination and challenge the status quo. From the outspoken advocacy of Muhammad Ali’s banter with the press to the quiet persistence of Curtis Flood’s refusal to be traded to another team “as a piece of property,”6 these trailblazers transformed their sports, their leagues, and the perceptions of people of color. They also impacted the bottom line, improved profits, and increased competition, eventually driving the complete integration of teams in every league throughout the next few decades.7

We’re more than just players—the impact of the rooney rule.

While athletes were able to break color barriers on the field,8,9,10,11,12 these same advances weren’t translating to the back office. Until the 1960s, all coaching positions in the major sports leagues were filled by white men.9,10,13,14,15 Until the 2000s, there were no team owners of color.16 Today, across the three biggest sports teams, the combined total number of nonwhite head coaches is six. This includes three in the NBA, two in the NFL, and one in MLB.17 The lack of representation in sports leadership sparked the creation of the Rooney Rule. The NFL adopted the Rooney Rule in 2003, and its influence has spread outside of the league. The rule states that NFL teams are required to interview ethnic minority candidates for head coaching jobs and, later, for general manager positions. There is a similar rule to help drive female diversity in front-office NFL positions.18 The rule’s fundamental goal was to ensure equal access to consideration for top positions for minority candidates.

Why then, after 17 years of the Rooney Rule, are only 12.5 percent of regular-season games coached by coaches of color?19 And why is the number of NFL head coaches of color the same (three) as it was in 2003?20 While it’s impossible to be present for hiring decisions within major sports teams, part of this reason is that the Rooney Rule only applies to head coaches. The candidate pool for head coaches is, quite obviously, other coaching positions. If quality candidates are lacking in assistant coaching positions, or if minority candidates don’t receive the same opportunities to fail as their white counterparts while keeping their jobs, then it becomes increasingly difficult to rise through the ranks and arrive at head coach.19,20 Many candidates also report that they feel they are fulfilling a quota, or checking the Rooney box,21 meaning exemplary candidates are discouraged and unable to live up to their potential. They could remain permanently stunted within the league, or they may leave entirely. The parallel with corporate America is clear: To have the best team, one must have true equity, from the hiring process through career development. Hiring the best should be the goal, and the best will, organically, be a diverse team. If this isn’t the case, then the rules of the game aren’t fair and must be rewritten.

Play like a girl—the growth of women’s professional sports.

Women have competed in college sports since the 1860s and in Olympic sports since the 1900 Olympic games in Paris.22 Until 1943, when the All American Girls Professional Baseball League started, no major professional leagues for women’s sports existed in the United States.23 After the end of World War II, women’s participation in sports grew; along with that participation, more opportunities opened for women to compete in professional sports. Since the 1980s, women’s professional leagues have emerged for basketball, football, soccer, and hockey.

When the WNBA premiered in 1996, it was initially an umbrella league for existing teams, but quickly grew into a professional league of its own. In the first year of the WNBA, it was able to draw more than 50 million viewers on three channels and grew quickly to reach audiences in 167 countries by 2001.24

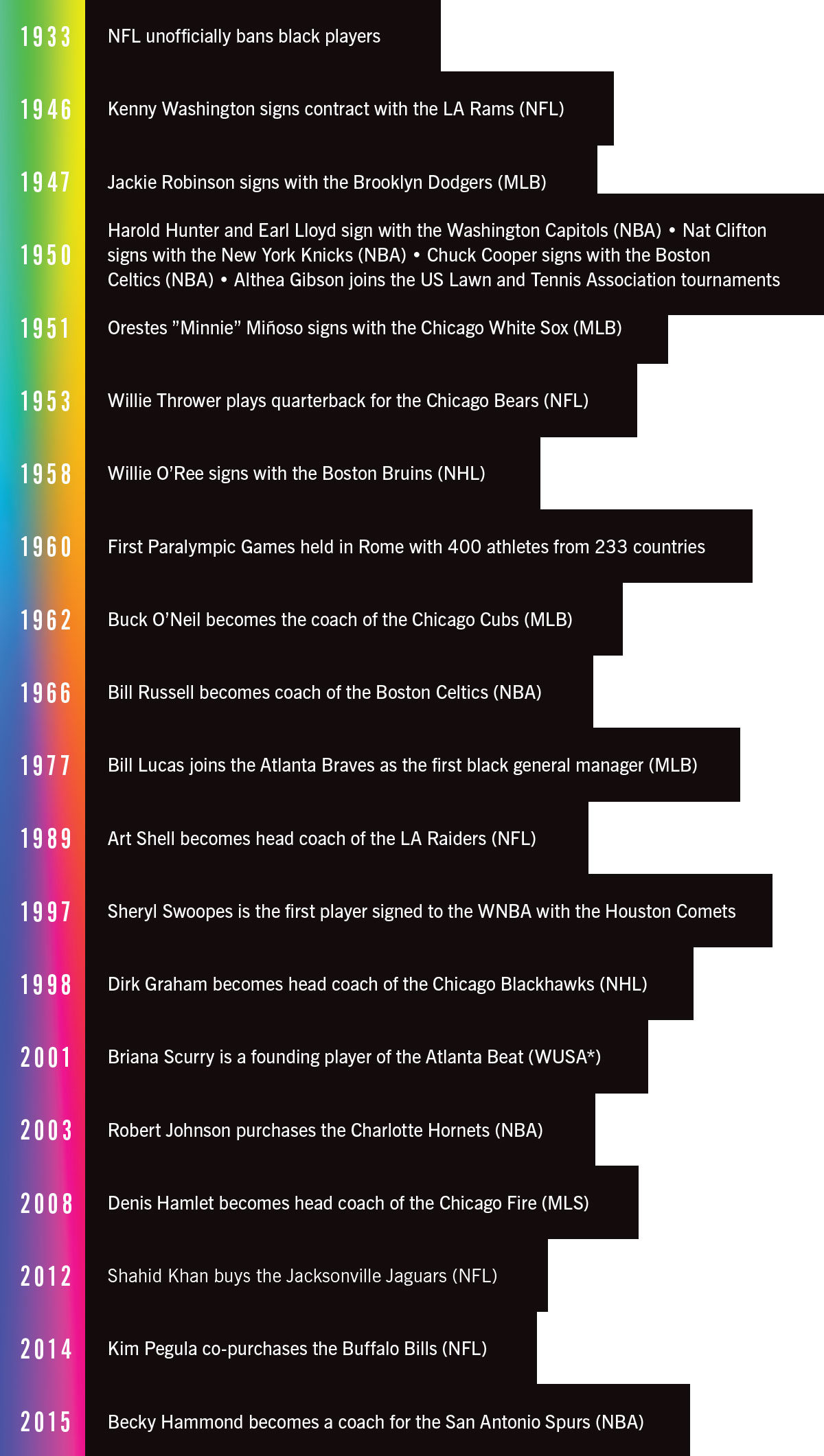

Despite the commercial success and popularity of the WNBA, player salaries—even with 2019’s increase—sit at about 20 percent of the minimum salary of their male counterparts.25 Last year’s number-one draft pick for the WNBA, Jackie Young, will gross a little more than $50,000 for this season. Her male counterpart, Zion Williamson, has an estimated salary of just under $10 million.26 Although the WNBA reports it is a money-losing league with estimated revenues of $25 million, only 20 percent of that revenue goes to the players. The NBA gives players nearly 50 percent of its $7.4 billion in revenue.27 At a minimum, the NBA redistributes its revenue more equitably and sets an expectation for the WNBA to do the same.

Women in corporate America often experience advocacy and sponsorship as a driver to success. The late LA Lakers superstar Kobe Bryant was a champion for women’s sports and helped drive the WNBA’s popularity in a meaningful way.28 Trailblazers such as Venus and Serena Williams joined Billie Jean King in forcing the tennis world to pay equal prize money to women and men in 2005.29 Andy Murray is an outspoken advocate for equality, on and off the tennis court.30 Everyone must work together to achieve true equality. True equality isn’t a zero-sum game. Equality helps create broader appeal and attract better players and more fans.

Don’t just make it pink. Women are fans, too.

The fan base of the five major league sports in America ranges from 30 percent (baseball) to 47 percent (football) female,31 with an average household income of almost $78,000.32 Revenue from licensed sports merchandise is projected to reach over $15B in North America by 2023,33 and women will account for a considerable portion of the sales. Major league sports teams have historically not catered to a diverse female audience, meaning that the significant purchasing power of female fans was not fully realized. Until 13 years ago, most fan apparel for women was pink and used a boxy, shorter cut from the men’s version. The mantra “pink it and shrink it” prevailed.34 This meant that a female fan had minimal options if she wanted to wear something team-branded to game day. The lack of options could make her feel like she wasn’t a valued fan, or that her favorite team didn’t view her as worth the investment. Depending on your age, you may know Alyssa Milano as Samantha from “Who’s the Boss?” or Phoebe from “Charmed.” What you may not know is that Milano is a sports fanatic. After declining to purchase a pink jersey at a Dodgers game in 2007, she launched Touch by Alyssa Milano. Touch makes branded apparel in team colors and fashionable cuts to cater to female fans who wanted options beyond a boxy jersey in pink. The new line of business was inspired: Female-fan apparel is now one of the fastest growing categories in sports apparel. Fanatics, a sports merchandise company that sells Touch, reported the third year of 20 percent-plus growth in its women’s business in 2018.35

fan demographics

Sources: the shelf, the wrap

It’s not a game without fans.

Sports is a booming business that relies on new populations to fuel its growth. Mindful inclusion of fans and players alike has allowed this growth to continue as leagues and teams focus on the fan experience. The sports market was worth $73B to the North American economy in 2019, with media rights making up almost $21B34in North America and $50B globally.36

The disruption of professional sports, a global and universal pastime, by COVID-19 highlights what a big role sports—professional or not—play in our culture. Through January and February, some leagues continued to hold soccer matches with fans wearing masks. As the virus spread, others, such as Inter Milan, held matches without fans and with minimal staff, keeping huge stadiums nearly empty. By the end of February, most global soccer games were canceled. Initially, American professional leagues were hesitant to cancel games, as their counterparts had done weeks before in Europe and Asia. Then, NBA player Rudy Gorbert tested positive for COVID-19, prompting the NBA to suspend its season on March 11, and the NCAA canceled March Madness the next day. Several other professional leagues followed suit all over the world, and the International Olympic Committee postponed some qualifying matches and, finally, canceled this year’s summer Olympics. The financial implications are massive, but they also created an opportunity to evolve the fan experience.

Average annual salary

Sources: Statista, AP News, ProBasketballTalk, NPR

To maintain business and revenue streams, sports leagues and teams are adding and enhancing viewing methods (streaming), playing to our collective nostalgia (broadcasting past games), engaging fans in new ways (e-sports), and adjusting how content is created (NFL at-home draft).36 While these innovations were in response to the restrictions posed by the coronavirus, they opened the door to better accommodations for fans who might not have been able to attend games in person even before the onset of the pandemic. Streamed content can be accessed for much less than the price of a ticket, and recorded content can be easily translated and captioned. Better accessibility can bring more fans to the game, even as it brings the game directly to such fans.

Who wants a hotdog? A crisis impacts everyone in sports, but not equally

The closing of stadiums and cancellation of games due to COVID-19 has impacted tens of thousands of people:37 players, owners, television and media personalities, lawyers, and a variety of other people who keep players safe and sane during the year. Many of these people are employed by players, teams, professional leagues, or the media and are salaried employees who will still be paid, even though games aren’t being played. However, a large group of people who support the sports community aren’t directly employed by teams or players: the food service and support staff of stadiums.38 These employees make games more enjoyable for fans by selling food, beverages, and merchandise, and by keeping facilities safe and clean. Without them, imagine sitting through nine innings without snacks, beer, and clean restrooms.

As contract or hourly workers, these employees will disproportionately feel the economic strain of halted games. Many (rich) players and (richer) teams have stepped up to help fill the gap caused by empty stadiums. While their actions are heartwarming, it only further highlights the inequality between the salaries commanded by players25,39,40 and the average minimum wages available to hourly American workers.41 Sports leagues and teams are huge, rich entities, but not every person involved is equally wealthy. It’s crucial for corporations to be inclusive of everyone involved in their business, because every employee plays a vital part in the customer experience.

rainbow laces aren’t enough—new frontiers in sports inclusion.

Sports continue to be vital in pushing boundaries and social norms through representation, and the LGBTQ+ community should be no different. As Patrick Hanley, policy & advocacy associate for Resource Center, an LGBTQ+ advocacy and community center, puts it: “If you want to be the hometown team, you can’t just represent one sector of the population. You have to be the team for everyone.” Beyond the morality of inclusion, the LGBTQ+ community has nearly $4T42 in buying power globally, and $1T in the US alone.43 There is a direct economic advantage to the social benefit true inclusion brings for this community, as shown by the prevalence of LGBTQ+ “pride nights” sponsored by teams across professional sports.

As LGBTQ+ athletes break barriers on the field, they also advance our discussions and understanding of identity. Student and professional athletes have forced schools and athletic commissions to address difficult questions of fair play and inclusion when it comes to transgender and intersex athletes. Due to the binary nature of the way that professional leagues and Olympic sports are organized, it is difficult for anyone who doesn’t identify as a cisgender (gender assigned at birth) male or female. Even those who do identify as cisgender male or female are sometimes scrutinized based on stereotypes disguised as societal norms.

Since 2009, middle distance runner Caster Semenya’s performance has been scrutinized and she has been exposed to a battery of physical exams and blood tests in the interest of “verifying” her gender and policing the level of testosterone she naturally produces.44 Semenya drew attention when opponents complained that she was “too fast” to be a woman when they lost to her in competition. Ironically, two of the gold medals Semenya holds are the result of opponents who were disqualified for doping. Nevertheless, she identifies as a woman, contends that she was born female and has subjected herself willingly to repeated testing and endured the humiliation that goes along with it to prove that she should be allowed to compete in women’s events. But every athlete is not afforded the same recourse.

In March 2020, Idaho’s governor signed two bills limiting the rights of transgender women and men in his state. One bill prohibits a change of gender on birth certificates while the other prevents transgender girls from competing as girls or women in sports.45 Combined, these bills effectively limit the definition of gender to biological sex and force transgender girls out of competitive sports, possibly taking them out of the talent pool and fan base forever. Corporations, illustrating that economics and equality go hand in hand, have been active in pushing back against discriminatory bills in multiple states.46

We got next! Accommodating mobility, hearing, and vision impairment in game play and spectatorship.

Sports play a huge role in our feelings of belonging in society. Whether we’re watching or playing, humans seem to naturally align with teams. We socialize around competition and form pieces of our identities around school and professional teams. As mentioned in the Spring 2020 issue of The Jabian Journal, “Economics of Inclusion: The Bottom Line Is Built on Inclusive Technology,”47 some accommodations are key to ensuring that those with mobility challenges and sight or hearing impairment can fully participate. Applying that concept to sports, not only should we enable participation as spectators, but we should include and encourage people to play and compete, using technology and equipment adaptation to enable full participation in game play.

While athletes are often perceived as strong, fast, exceptional, or even physically superior to the average person, the truth is that anyone can be an athlete. Unfortunately, perceptions and stereotypes can crowd people out or make some feel like they are excluded from competition, especially those with physical impairments. Fortunately, these perceptions are changing. Media exposure of athletes with physical impairments is increasing and assistive technologies are constantly improving, providing more options for adaptive athletes. This improvement in accessibility enables new lines of business via adaptive leagues. Demand for and popularity of accessible sports have spiked, witnessed by a threefold increase in ticket requests at the Paralympic Games between London 2016 and Tokyo 2020 (now 2021).48 This inclusion opens up new customers in the athletes themselves, and in the fans who buy tickets, content, and merchandise.

Sports mirrors the real world because sports IS the real world.

Sports has played a pivotal role in the societal evolution of perceptions of race, ability, gender, sexual orientation, and gender identity. Sports teams and leagues have grown and prospered by pushing the boundaries of social acceptance and welcoming in new players who bring more dollars, through sponsorships, advertisements, and direct spending. Because of its need to constantly evolve, sports is a living business case for how inclusion can positively impact a company and an industry, and the financial challenges that result from resisting the move toward equality.