“Quiet quitting” became a thing in early 2022 when several TikTok videos went viral espousing the idea of doing less at work but not actually leaving your job. Today, a quick Google search reveals thousands of articles, blogs, and social media posts dissecting the phenomenon. And, like most subjects in our supercharged media landscape, quiet quitting has become a hot topic of debate — everyone has an opinion. Less clear, however, is an actual definition of the term and how quiet quitting is different from, say, scaling back at the office to achieve a better work-life balance.

Even more important, what should leaders make of quiet quitting? Is it good or bad? How can they identify and address it before it becomes a problem, if it is a problem at all? And how do strong managers find ways to create a dialogue between employers and employees that results in positive outcomes and healthier work environments?

Leaders who observe a change in an employee’s output or results may have a worker who has checked out and is ready to leave, or they might have an employee simply scaling back to a more reasonable pace. Unfortunately, the world seems to have lumped both into the category of “quiet quitting.” In this article, we provide a framework for leaders to assess which situation they’re in and what to do about it.

Quiet Quitting for Employees. Quiet Firing and Quiet Hiring for Employers.

The idea of “quiet quitting” went viral in a world exiting a global pandemic. Companies were struggling to find the right balance between virtual and in-person work while employees were struggling to recalibrate their lifestyles, reintroduce commuting, and make time to once again socialize with colleagues. Top that off with a workload that had increased (in the employer’s favor), and you had a workforce that was tired, overwhelmed, anxious, and uncertain about the future. The global shift in work created a work-life balance crisis for a sizeable portion of the workforce.

From the employee perspective, there’s a positive side to quiet quitting aimed at “scaling back,” “setting boundaries,” “right-sizing your work,” and “recovering from burnout” — all personal management strategies that should be viewed in a positive light. Achieving work-life balance has been a goal of enlightened companies concerned about employee engagement for years. At the same time, the idea of “quitting in place” or “doing the bare minimum” has also been around for years. So, is anything really new?

The answer is yes, but it’s not quiet quitting. It’s on the employer’s side of the equation. As a result of the quiet quitting trend, employers have started engaging in two new behaviors of their own: “Quiet Firing” and “Quiet Hiring.”

Quiet firing is the idea that managers quietly ignore weaker employees until they miss a key deadline or series of deliverables and can be placed on a performance plan. The goal is to drive the employee out by getting them to quit voluntarily.

Quiet hiring, meanwhile, occurs when employers give extra work (probably the work that belonged to those who quietly quit) to more engaged employees without additional recognition, promotion, or compensation until they burn out and leave. While the ethical nature of “quiet quitting” depends on the employee’s true intentions — have they really checked out or are they simply readjusting their lives? — that of quiet firing and quiet hiring is more clear-cut. We find both unethical on the part of the employer.

A Framework for Assessing Quiet Quitting

Performance, effort, and ethics all play a role in the conversation about quiet quitting, quiet firing, and quiet hiring.

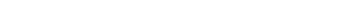

To determine whether a direct report is quietly quitting or simply trying to achieve work-life balance, it’s important to understand how employers and employees have traditionally assessed performance. As employers, we can only assess the performance of an individual based on the results they achieve, the quality of their work, and the environment their behaviors create. Employers typically measure or evaluate employees on a spectrum that looks something like this:

This is a standard performance evaluation spectrum. With this spectrum, employers are evaluating performance or results — the tangible and intangible outcomes of an employee’s work. It is important to emphasize, however, that how the work gets done is also critical. Employees should be expected to do their work in a way that promotes employee engagement across the enterprise. An employee who “does not meet expectations” will eventually find their job at risk. Employees who “meet expectations” will remain in their roles, but the likelihood of promotion or increased compensation is diminished. Employees working “above expectations” are moving the company forward in growth and/or product or service quality.

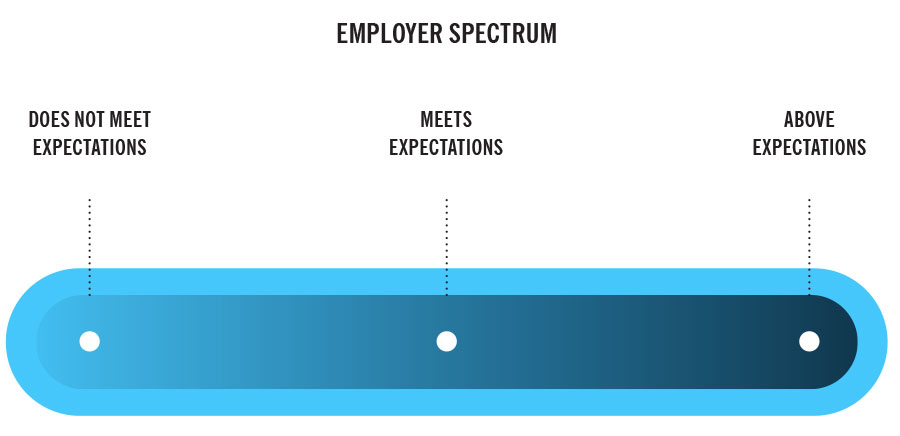

Employees, on the other hand, often evaluate themselves based on the effort they put in. An employee who is “quitting in place” is not meeting the expectations of a role because they have one foot out the door, are looking for a new job, and/or are fine with being fired. “Meeting expectations” means doing what is required of the role, but not much more. “Sustainable high performance” is doing what is required of the role but contributing in a way that moves the organization forward from a growth or quality perspective. And finally, “unsustainable overachievement” involves putting forth a level of effort over and above what is expected and requires bandwidth well beyond what is considered working reasonable hours.

Quiet Quitter or Deliberate Downshifter? How to Address Each Once You’ve Identified Them

It’s important to consider both spectrums when addressing employee engagement, as well as remember that they operate independently of one another. Employers should evaluate results and have consistent conversations with their employees about the level of engagement in their work. They should resist the temptation to make a judgment on whether someone is putting in enough effort and using that perceived level of effort to evaluate their performance. What should matter to the company are the results that that employee delivers and the way in which those results are achieved. If the employee is delivering good work and promoting a positive work environment, then everyone should be satisfied. Only employees truly can evaluate their own level of effort.

On the employee spectrum, quiet quitting can (often wrongly) be perceived as simply moving from left to right along the spectrum. Employees who move from “unsustainable overachievement” to “sustainable high performance,” or from “sustainable high performance” to “meeting expectations,” however, may simply be bringing their work and life into balance and alignment for that moment in their lives. It’s important to also consider that everyone goes through phases at work where “unsustainable overachievement,” and the commitment it requires, is warranted, so long as a downshift occurs before burnout sets in.

When situations outside of work shift the balance to life, we naturally downshift. For example, someone working in a state of “unsustainable overachievement” while managing a new baby at home is at substantial risk for burnout. It’s wise to downshift to make room for these significant life events. That’s not an unethical downshift; it is enlightened self-awareness. However, some recent media coverage and some employers would label these employees as quiet quitters, which is unfair. Quitting in place, however, crosses the line into unethical behavior.

In the end, whether quiet quitting is good or bad comes down to the ethics behind the decisions employers and employees make. We can all agree that quitting in place is ethically wrong. Quiet firing and quiet hiring are ethically wrong. But simply downshifting one’s level of effort to achieve balance in life is a best practice. That downshift can result in higher engagement and even increased productivity. This means that some people’s definition of quiet quitting — moving leftward on the employee spectrum — can end up moving them left to right on the employer spectrum toward better results.

Communication Is Key When Facing a Quiet Quitter

As a leader, conversations and communication are key when confronted with a “quiet quitting” situation. First, employers need to be comfortable accepting that it is okay for an employee to fall anywhere on the employee spectrum except “quitting in place.” Taking the time to understand where an employee feels they are on the employee spectrum and being open to periodic upshifts and downshifts in work effort will result in more engaged employees and better performance for the business.

However, leaders who notice a significant downgrade in an employee’s performance and worry that they may be quitting in place should have a conversation with the employee. Working with the employee to either help them accommodate their personal needs or find a new role inside or outside the company is a much more engaging and ethical way to handle these situations, especially in an uncertain economy.

In the end, though, managers should stop talking about quiet quitting as a negative and instead use the framework outlined above to create a dialogue between employers and employees. Only when there is open and honest communication about the company’s goals and an employee’s level of engagement can we achieve positive outcomes and a healthier work environment.