Tim Teamleader receives the latest draft of “five strategic imperatives” from his boss. It’s mid-September and the few pages represent the latest thinking from the executive team regarding the upcoming year’s strategic plan.

Tim reads the document as if it were an automated e-newsletter with a few thought-provoking points good for improved hallway small talk. He decides, like he has the past couple of years, to wait until he is given his initial budgetary number for next year before beginning his strategic portfolio planning process.

When the initial number arrives, it is early October. He pulls the latest list of in-flight and upcoming initiatives his group is supporting. Starting from the top, he calculates the running total cost of the list, and draws a line where his budget number runs out. Over the next couple of months, he’ll reference this list and adjust it as new requests are added or as the scope of the initiatives undergoes major adjustments. Tim will make at least a couple of presentations to executives who might summarize his list in their presentations to the organization’s funders.

In early to mid-December, when it’s time to set the final strategic portfolio budget, Tim submits his latest thinking in the organization’s chosen format and budgeting tool. He calls his team together to give them the good news: “Next year’s plan is finalized, and we got most of what we wanted.”

Back in September, Tim could have used the first set of strategic goals as a basis for a planning process involving his peer leaders and his team. Instead, he operated under the assumption that, because inputs to the plan would change and a plan could never be perfect, his peers and his team would benefit more by saving time than by engaging in a formal portfolio development process. Did Tim miss opportunities to test the feasibility of his portfolio and ask for the resources required to execute it? Were there preventable and predictable risks inherent in his portfolio because it was not assessed against available resources and existing roadmap dependencies such as product road maps or known customer impacts? Finally, and perhaps most importantly, did he miss an opportunity to engage and align his leaders, peers, and team members through a collaborative portfolio development process?

It seems there is always less time available than required to complete one’s work. But if done right, the benefits of a collaborative, efficient, practical portfolio planning process outweigh the time required. In addition to mitigating risks, generating team buy-in can set a foundation of engagement to be maintained and called upon throughout the year. After pondering these same questions, Tim decides to try a new approach next year.

The most important ingredients in the success of any venture are usually the managers who are responsible for it.… The rigor and quality of the business case play a crucial role, but equally if not more important are interpersonal factors such as interaction at meetings, the ability to answer questions, and harmony of thinking.

Planning and communicating are responsibilities of leaders

The nature of business strategy requires flexibility and autonomy at the team level. Thorough assessments of the market opportunity, exhaustive reviews of an organization’s or a team’s capabilities, and detailed cost-benefit analyses of specific projects can lead to a great set of goals.

However, organizations often fall short of success because team leaders don’t own the responsibility of setting a plan and engaging their teams. Working toward an inspiring goal with the wrong plan is certainly frustrating. But the more tragic scenario, in which leaders avoid developing a best guess plan, avoid measuring results against that plan, and avoid holding themselves and their teams accountable, leaves team members incapable of seeing the value of their contribution. Of course, the opposite is true as well. A public and collaborative review of a team’s progress against a plan provides an opportunity to adjust given the latest information and to communicate to each individual where they fit in and how their goals may have changed.

As Patrick Lencioni writes in The Three Signs of a Miserable Job, “Everyone needs to know that their job matters…. Without seeing the connection between their work and the satisfaction of another person or group of people, an employee simply will not find lasting fulfillment.”1 Too often, corporate strategies are set through a series of siloed discussions (C-suite with the board, C-suite with finance, finance with department leads). Those strategies are handed down to department leads, who are then measured by a finance group with an eye toward the accounting significance of every business transaction, rather than as progress toward strategic goals. That approach does make sure “trains run on time,” but it misses a significant opportunity to bring a team together and motivate them toward a common goal.

In Peter Drucker’s well-known article “What Makes an Effective Executive,” three of the eight common responsibilities of an effective executive were taking responsibility to develop a plan, taking responsibility for their decisions, and taking responsibility for communicating the plan.2 The space between strategy development and strategy execution is a critical opportunity for leaders. Done right, the exercise of assessing an organization’s capabilities, assessing the resource feasibility of a portfolio, and scheduling initiatives acts as a team alignment mechanism.

The most important components of a portfolio development process

According to accountant, business consultant, and author John Tennent, “The most important ingredients in the success of any venture are usually the managers who are responsible for it…. The rigor and quality of the business case play a crucial role, but equally if not more important are interpersonal factors such as interaction at meetings, the ability to answer questions, and harmony of thinking.”3

Checking back in with Tim, it’s the following year. He now seeks to answer these questions by building a sound and complete portfolio development story, ready for executives, key partners, and new team members during the planning process and throughout the year.

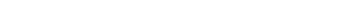

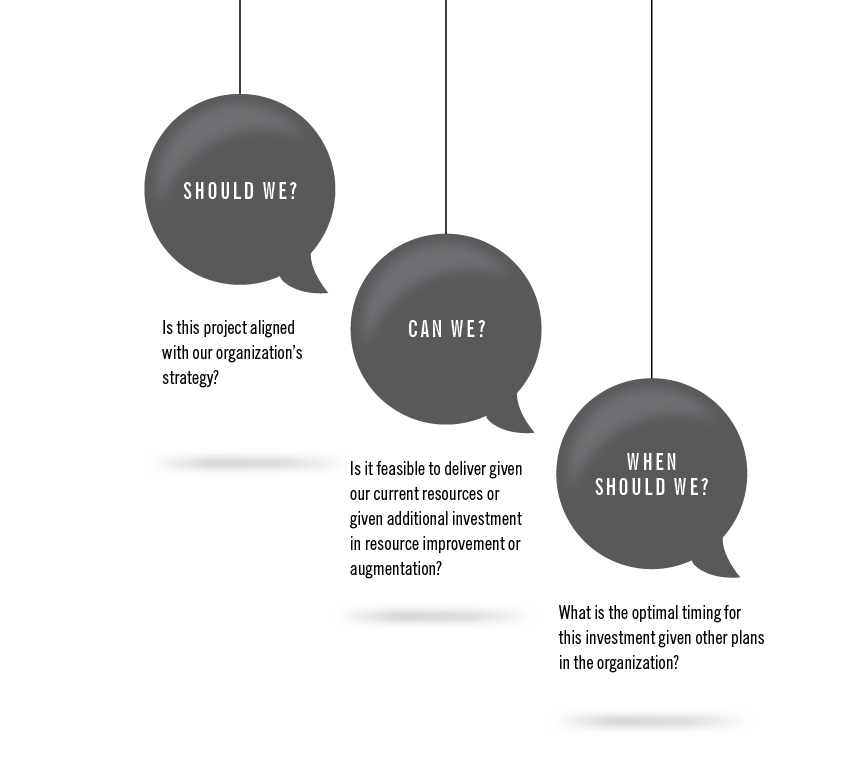

A leader doesn’t require significant investments in technology to lead an effective and collaborative portfolio development effort. Instead, a straightforward process that answers the following questions is required:

Investment selection: “Should we?”

The first phase of a portfolio development process focuses on filtering out requests that do not align with the organization’s goals and prioritizing the rest so decisions can be made later regarding the allocation of limited resources.

In our example, when Tim received a draft of the company’s goals (whether high-level and based on guiding principles or detailed with accompanying metrics and milestones), he had a rubric for grading investment opportunities. Assessing and documenting the alignment of initiatives would be difficult only if a strategy didn’t exist. If that is the case this year, Tim will need to draft his best understanding of what is needed for the company, then communicate that to his superiors and peers before moving forward. This step is critical because “harmony of thinking” starts here. By documenting his understanding of the organization’s goals and his team’s role in contributing to those goals, Tim will drive rich, insightful conversation with superiors and his team. Even if he doesn’t achieve perfect clarity and alignment up and down the organizational structure, the charge of a leader is to set direction.

With this in hand, Tim can create a spreadsheet scoring how well each initiative aligns with the organization’s goals, subjectively assigning scores from 1 to 5—1 being not aligned at all and 5 being perfectly aligned. With that, he can quickly prioritize a large list of requests or ideas.

Beyond the subjective alignment score, he can use several other methods to differentiate projects based on their financial value. These evaluations include estimations of payback, net present value, discounted payback, and internal rate of return. For clarity on the strategy to be used as a proposed filter for initiatives, Tim will align with the CEO and executive suite. For the financial valuation methods, it’s best that he collaborates with the finance team to ensure that his final portfolio has the fundamental backing of the group that will approve his budget. Using strategic alignment and estimated financial benefit will produce a well-prioritized list of initiatives.

Feasibility assessment: “Can we?”

Assessing the team’s ability to deliver against a strategic plan is the aspect of portfolio development that is the most tempting to disregard. For many, looking for reasons a strategy won’t work or, at least, can’t work within the target timeline may feel like working against the interests of the company. However, strategies fall short all too often because they are developed with a limited set of variables (sometimes only budgeting estimates are considered, as in Tim’s original approach).

Feasibility analysis is the grounding of strategic theory in the reality of limited resources. Those resources include a team’s skills, resource capacity, and budget. The realization that a strategy is unrealistic because its execution would require external capacity, specialized skills, or expensive investments in technology is not a popular message to deliver, but it is a message best delivered early.

Given a prioritized list of initiatives, Tim needs to quantify the demand for each of his team’s key resources. When determining variables to assess, timeliness of estimation and ease of analysis are crucial. Throughout a portfolio development process, several what-if scenarios will be proposed and new information will be discovered that will affect the prioritization of initiatives. Pausing collaborative planning sessions for a few days to rework assumptions will stall momentum and discourage the portfolio development process altogether.

The first ingredient to a nimble and robust process is a standard estimation method. Borrowing a concept from Agile Delivery, T-shirt sizing is an efficient technique to involve several team members in determining the relative effort of initiatives. Tim will do well to make sure the member of his team who is ultimately responsible for executing the initiatives has the final say on what resources and how much of each the T-shirt sizes represent.

After estimation sessions are held, Tim can adjust the first draft of initiative scheduling and determine intermediate and long-range resource needs. If sourcing efforts need to ramp up for high-demand resources or training and transition of underused resources is required, action can be taken proactively. While requests for additional budget or final hiring plans may need to wait until later in the process, Tim can plant seeds with his executives early to let them know that those requests may be coming.

Scheduling and scoring: “When should we?”

To provide his team a portfolio road map, Tim must complete putting the portfolio on a calendar and quantify its value. Because resource capacity planning was inherently included in the feasibility assessment phases, a first cut at scheduling exists.

This phase begins by understanding the important potential collisions or dependencies with the current portfolio and other important road maps such as product road maps and associated marketing plans or technology road maps. In addition, the anticipated stakeholder-change impacts from Tim’s portfolio can be quantified by using a “high, medium, low” for key groups such as internal departments, suppliers, and customers. The point of assessing the scheduling of initiatives against these other plans is to identify any major risks related to overwhelming a specific stakeholder (e.g., if a new customer relationship management system is scheduled to roll out at the same time as three major product releases). While the feasibility assessment was focused on the supply of initiative execution resources, scheduling is focused on the supply of a customer’s (internal or external) capacity for change.

The last step in the scheduling and scoring phase is to quantify the anticipated return on investment from the current and alternative portfolio scenarios. Although optional, it is common for leaders to ask for a comparison between strategic approaches: “What if we started the year by building X and then came back to Y in late summer?” By quantifying the benefits of each scenario, a strategic direction can be determined. Using the estimated return of the initiative and prorating it for the days remaining in a standard analysis period after an initiative is completed (e.g., trailing 24 months after the budget start date) provides a straightforward financial answer to the question. While some complexities are certainly avoided with this approach, using this method will provide quick, directional feedback to leaders. At this point, Tim would very likely update initiative inputs and leader prioritization and, of course, have several rounds of rich discussion with his leaders, peers, and team members.

“In every nation that keeps reliable television ratings, the most watched live broadcast in the past 50 years is a match between two sports teams…. The fact is that in the history of human events, nothing draws a larger and more diverse audience than two elite groups of athletes competing…. Part of what makes us human is the desire to join a collective effort.”4

That quote from Sam Walker’s The Captain Class puts in perspective the longing by all humans to experience a passionate pursuit of a goal that can be measured objectively. The most popular and memorable sports matches are those in which teams are evenly matched and the outcome hangs in the balance until the very end. Understanding how a team’s resources match up against the demand for those resources helps create a similarly compelling environment for business teams—one in which an honest best effort will be required to achieve a collective goal.

The preceding process will be new for Tim and his team. The education and awareness it will provide by making the planning process transparent are significant. While everyone is motivated differently and many individuals prefer not to be publicly praised or appraised, the desire to be a part of a team pursuing a worthwhile goal is ubiquitous. That’s why the development of a team plan is worth the effort. The opportunity to invigorate a team, clarify everyone’s role, and clarify their impact on collective goals is frequently worth more in terms of employee engagement than in the execution of results.

- Lencioni, Patrick. “The Three Signs.” The Three Signs of a Miserable Job, Jossey-Bass, 2007, pp. 221–222

- Drucker, Peter F. “What Makes an Effective Executive.” Harvard Business Review, June 2004

- “Investment Appraisal.” Guide to Financial Management: Understand and Improve the Bottom Line, by John Tennent, The Economist Books, 2018, pp. 182–185

- “Part III: The Opposite Direction: Leadership Mistakes and Misperceptions.” The Captain Class: the Hidden Force That Creates the World’s Greatest Teams, by Sam Walker, Random House, 2017