Enterprise risk management, or “ERM,” is often recognized as a corporate governance solution to protect shareholder interests, save companies millions of dollars, prevent catastrophic loss, and protect the brand. The very mention of ERM, however, can stir spirited reactions within senior leadership ranks and among board members.

Enterprise risk management, or “ERM,” is often recognized as a corporate governance solution to protect shareholder interests, save companies millions of dollars, prevent catastrophic loss, and protect the brand. The very mention of ERM, however, can stir spirited reactions within senior leadership ranks and among board members.

Often, this is because they’ve had negative experiences with ERM: failed or inadequate implementations, lack of understanding, or misaligned priorities and interest around risk management objectives.

Yet as brands suffer substantial damage through a loss of intellectual property, cyber-related incidents, and other mishaps often cited in the news, federal regulators, institutional investors, and others are requiring companies to ensure that their risk governance is adequate. Along with those assurances, they also want to know brands are identifying and managing the right risks.

On the surface, ERM seems simple enough: risk management at the enterprise-level focusing on enterprise-level risks. However, ask a dozen experts to define ERM and you are likely to get at least a dozen or more explanations. For some, ERM is a philosophy. For others, it’s a methodology, a set of tools, or an ethos. Still others argue that it is nothing more than a regulatory requirement or a check-the-box activity.

Whatever you consider ERM to be, one thing is clear: Most ERM implementations fail to deliver on expectations. Often, organizations fail to recognize the organizational change risk associated with the implementation. Or, they rely on advisors with little more than academic knowledge of ERM frameworks such as COSO (Committee of Sponsoring Organizations) and ISO 31000 Risk Management.

A working knowledge of a standard like COSO or ISO 31000 is not difficult to achieve. The difficulty is in understanding how to tailor and apply these “best practices” for the business and how to implement these practices toward a sustainable contribution to the organization. Meeting a set of requirements will certainly check the compliance box but has little value otherwise.

As a result, organizations with a mindset toward upside risk management are more readily capable of implementing solutions that provide a positive ROI and protect the business through stronger performance against their peers, especially in down markets. This is best achieved utilizing experienced professionals who have more than an academic knowledge of ERM. They need experience in actually designing, implementing, and owning the process with positive outcomes.

Organizations seeking upside risk management must address these factors with a mindset toward operational capability:

- Board and C-suite ownership and accountability

- Strong internal and external risk identification capabilities

- A solid risk management strategy

- Effective communication up, down, and outside the organization

- Institutionalization throughout the organization

- Solid risk management experience

Today, many ERM practitioners are focusing on hot topics such as “risk appetite,” “culture,” and “strategy.” None of these topics can be meaningfully implemented without building the infrastructure necessary to support them. Many organizations today, however, are making these mistakes, often at the hands of misguided advisors.

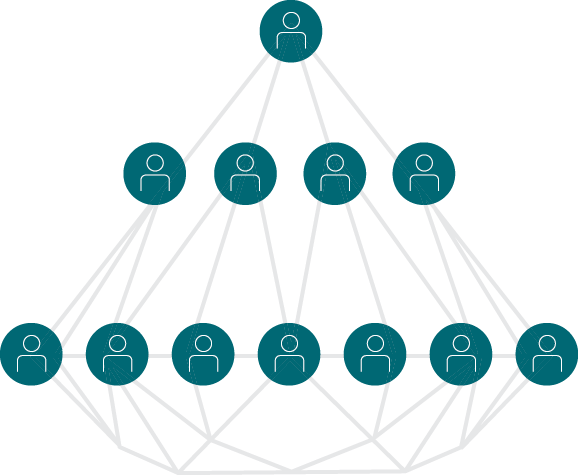

To create value from ERM, leaders require a roadmap. It is a journey, not a whistle stop. To be successful, the roadmap should follow a systems-engineering mindset. ERM is a business system consisting of 1) a risk organization; 2) governance; and 3) system tools, all integrated to help protect the business. Thinking about ERM in these terms allows the organization to create an effective and sustainable ERM solution.

It also allows the leadership to take that same solution and apply it throughout the organization to manage risk at the appropriate level, whether at the individual contributor level or with directors and officers.

Examples where integrated ERM can make a marked difference include risks such as cybersecurity, supply chain disruption, product development, business continuity, crisis management, and many more, any of which could be devastating to the organization. All these risks may seem daunting or even impossible to manage. Some organizations do it with ease, reporting the risk information at appropriate levels and gaining valuable predictive insights that support decision-making at all levels.

To successfully build a strong and sustainable ERM program, here’s a deeper dive into five traits of an upside risk management capability.

1 Board and C-suite ownership and accountability

1 Board and C-suite ownership and accountability

ERM without a “mandate from the top” will never be more than a compliance “check the box” exercise and a “tax” on the business. For publicly traded companies and non-profits, this mindset may also expose directors and officers to liability that can damage their personal reputations, leading to fines, penalties, and, in some cases, jail time.

Sarbanes-Oxley, Dodd-Frank, and other regulations require directors and officers to ensure that their risk management capabilities are adequate and that the organization has identified and managed the right risks. While in some cases the regulation may not be explicit, the fiduciary responsibilities around risk management are real and should be understood. Regulation alone should be enough motivation to provide a mandate from the top, but ethically speaking, it’s also the right thing to do for stakeholders, employees, and customers. Nevertheless, many companies are still ignoring formal ERM systems.

A mandate from the top often implies that directors and officers provide active support for ERM. To make ERM actionable, they must provide adequate funding, establish clear roles and responsibilities, and set expectations for accountability. That typically means funding the risk management organization and its activities—including procuring and maintaining a risk management information system. Addressing this one trait in ERM also sends a strong message to institutional investors and other stakeholders that can produce positive results for performance.

2 Strong risk identification capabilities

2 Strong risk identification capabilities

Without board and C-suite ownership and accountability, organizations will not have adequate risk identification capabilities. Ownership and accountability establish the expectations for identifying internal and external risks to the organization, and these activities are overlooked or ignored when executive mandate is absent.

Setting expectations and promoting the need to identify risks will often lead to a culture that proactively thinks about risks when addressing every major decision, product idea, investment, etc. Thus, an environment promoting and fostering an expectation to think about, identify, and manage risk will see an increase in user adoption and effectiveness of ERM. Conversely, an environment that “shoots the messenger” or denigrates employees for bringing up risk, or marginalizes employee efforts in risk management, will quickly create a toxic culture that avoids identifying and managing risk. These actions destroy a positive risk culture. Signs of a mature and healthy risk identification culture include:

- Well-defined and maintained corporate risk governance

- Frequent risk committee meetings

- Intentional risk identification and assessment events

- Evaluation of strategic objectives for risk

- Strong board engagement in understanding risk capabilities and the risk profile

- Employee and external stakeholder inclusion

Another factor involves how well risk identification efforts are integrated with other functions like internal audit, general counsel, information technology, supply chain, continuous improvement, and others.

Within these functions, it is important that each respective leader independently identify and manage their risks and appropriately elevate them to the C-suite. This portfolio management and roll-up of risk is found in mature and capable ERM systems. It consists of a risk tool capable of managing a portfolio of risk information; defined risk escalation criteria; and a common, integrated risk process. A common risk process should include a purpose statement, scope, standard risk process, key roles and responsibilities, and stakeholder integration. This process and the risk tool are applied across the entire organization, from strategy and finance to operations, HR, and IT.

Along with the risk tool and common process, leaders should explore, develop, and perfect methods to identify risk. Interviewing key company stakeholders is standard practice—including external subject matter experts. Metrics from key risk indicators, brainstorming,

risk deep-dives, external reports, third-party evaluators, etc., can enhance risk information, analysis, and decision making.

3 Solid risk management strategy

3 Solid risk management strategy

The keys to a solid risk management strategy are execution and application. When a risk is identified, so must be the strategy for handling it. Typical strategies include acceptance, avoidance, mitigation, and transference of risks.

Every business or industry has inherent and intrinsic risks. Typically, these are the risks we accept as part of doing business. Formally tracking all accepted risks, whether inherent or not, is critical to understanding the organization’s total financial exposure.

Sometimes a risk can be avoided. An example of this might be working with regulators to change or enhance laws and regulations to avoid negative effects on the business or industry. Often, a cost is associated with this strategy, but the outcome can be favorable for the organization’s long-term health. Industry organizations and lobbyist efforts are examples of ways to affect regulations.

The risk committee’s decision to mitigate a risk is usually followed by dedicating budget toward agreed-upon steps that reduce the likelihood or impact of a risk. Leadership should report expenditure of resources and the execution of the steps to risk management stakeholders as part of the accountability structure. Leaders should also ensure that the mitigation steps are achieving the desired expectations. When mitigations do not meet expectations, adjustments may be necessary.

Insurance is an example of risk transfer. In many cases, organizations may depend too heavily on insurance and not enough on a more comprehensive approach—including other strategies. Insurance is a necessity for running a business. Making sure the risk is adequately transferred requires excellent brokerage relationships, actuarial analysis, and in some cases, third-party legal reviews for a non-advocate opinion.

For example, companies are increasingly insuring against cyber risk. Many, if not most, cyber policies may not pay out as expected thanks to poorly structured insurance agreements. Often excluded from some policies are items such as breaches identified as “state sponsored” or the result of a “terrorist” organization. Another exclusion that may prevent payout in some cases is the company’s inability to provide evidence that it took necessary and appropriate actions to prevent cyber breaches in the first place. Some indicators of this may be multiple breaches over a period of time with similar exploitations, lack of investment in protections, lack of PIN and vulnerability testing, and lack of transparency around breaches when they do occur.

No matter the strategy or combination of strategies an organization chooses, it is necessary to document each of the steps to execute the strategy. In most cases, Fortune 500 companies included, ERM risk information is kept and maintained on a spreadsheet. Unfortunately, firms are slow to adopt formal risk tools, sometimes referred to as risk management information systems (RMIS), partially because of the cost, though companies are starting to see the benefits.

Benefits include deeper analysis of risk drivers; ability to correlate risk impacts across multiple areas and products of the business for strategic decision making; risk insights; and proactive indicators to protect the organization. The right RMIS helps a company meet compliance requirements and provides decision-making information capable of setting the organization apart from its competitors.

4 Effective communication

4 Effective communication

If leaders look at ERM as merely a compliance process, they will never realize the true benefit of ERM and risk management in general. Shifting perspective, ERM and risk management are, more broadly speaking, a communication process that enables executives to more effectively achieve the strategies of the business.

If risk management is a disciplined approach to identifying, assessing, handing, and monitoring risks, what is the primary reason for doing so? The primary reason is to identify threats quickly, establish countermeasures, and strategically grow the organization. To successfully achieve this, efficient communication of those risks is fundamental to the process.

Well thought-out and established governance is one factor in effective communication. It usually establishes the tempo for risk committee reviews, board reporting, structured risk identification events, etc. In other words, it sets the expectations, but not the quality.

Quality risk communication starts with quality risk information and the ability to take that information and present it in many forms. While most companies focus on the top 10 risks

by overall score, other arrangements are equally insightful, if not more so. For example, a company could consider its top 10 risks by impact, likelihood, management effectiveness, product or project, country or region, function (IT, HR), and so forth. For advanced decision information, some tools even provide “clustering” of risk drivers and events, which lends senior leadership powerful and very strategic decision capabilities.

As previously implied, simply looking at an ordinal list of risks can emphasize the wrong priorities. To stratify risk information into limitless views based on business needs, leaders must discard spreadsheets and use a dedicated RMIS solution. In addition, these systems automate the process of sending risk information to stakeholders and recording information that is useful to internal auditors, who often provide internal assurance of compliance with regulatory requirements.

5 Institutionalization

5 Institutionalization

In recent years, much has been said about risk culture. Some define it as a “mindset” toward risk. But how do you measure that? And what does that mean? Improving risk culture is really about institutionalizing the process throughout the organization, setting the expectations for identification, managing and reporting the risks, and creating an environment that welcomes rather than discourages risk management.

As mentioned earlier, this process starts with a risk management framework. The framework should be designed to guide the policies and processes necessary to effectively manage risk. Without good policies and processes, accomplishing user adoption of risk management activities will be difficult if not impossible. In addition, repeatable and sustainable results will also be hindered.

To overcome these challenges, a common risk process defined in a risk management plan—in compliance with the corporate risk policy—is a good first step. This plan should include scope, applicability, key roles and responsibilities, process flows, meeting cadence, and reporting and metrics requirements.

When the process and plan are written correctly, the same document can be used across any functional component of the organization. The only real difference would be the types of risks assessed. For example, cybersecurity risks will have different use cases and threat analysis than HR risks. However, the two functions may have a mutually exclusive risk that affects other functional area.

Because of these complexities and the need for functional areas to be able to manage their own risks, RMIS solutions become quite handy thanks to their ability to manage a portfolio of risks as well as multiple effects.

When leaders become aware of the value of this information in achieving the results demanded of them, they do not hesitate to incorporate risk management into their daily routine. This is when risk management becomes institutional. It is also when an organization achieves a risk culture that is sustainable, proactive, and not burdensome or costly.

With the attributes of an effective ERM capability covered, the next question is how to implement it? At Jabian, we advocate a systems-engineering approach to ERM, as it provides a reliable method to tackle some of the largest risk management governance problems and provides solutions that integrate the whole organization into one cohesive information system.

In addition, such an approach has saved tens of millions of dollars through risk avoidance, efficiencies, and lower insurance premiums, including Total Cost of Risk (TCOR). Through this methodical process design, firms can take a framework like ERM and truly leverage its potential and capabilities to protect shareholder value and achieve objectives.