Changing Habits

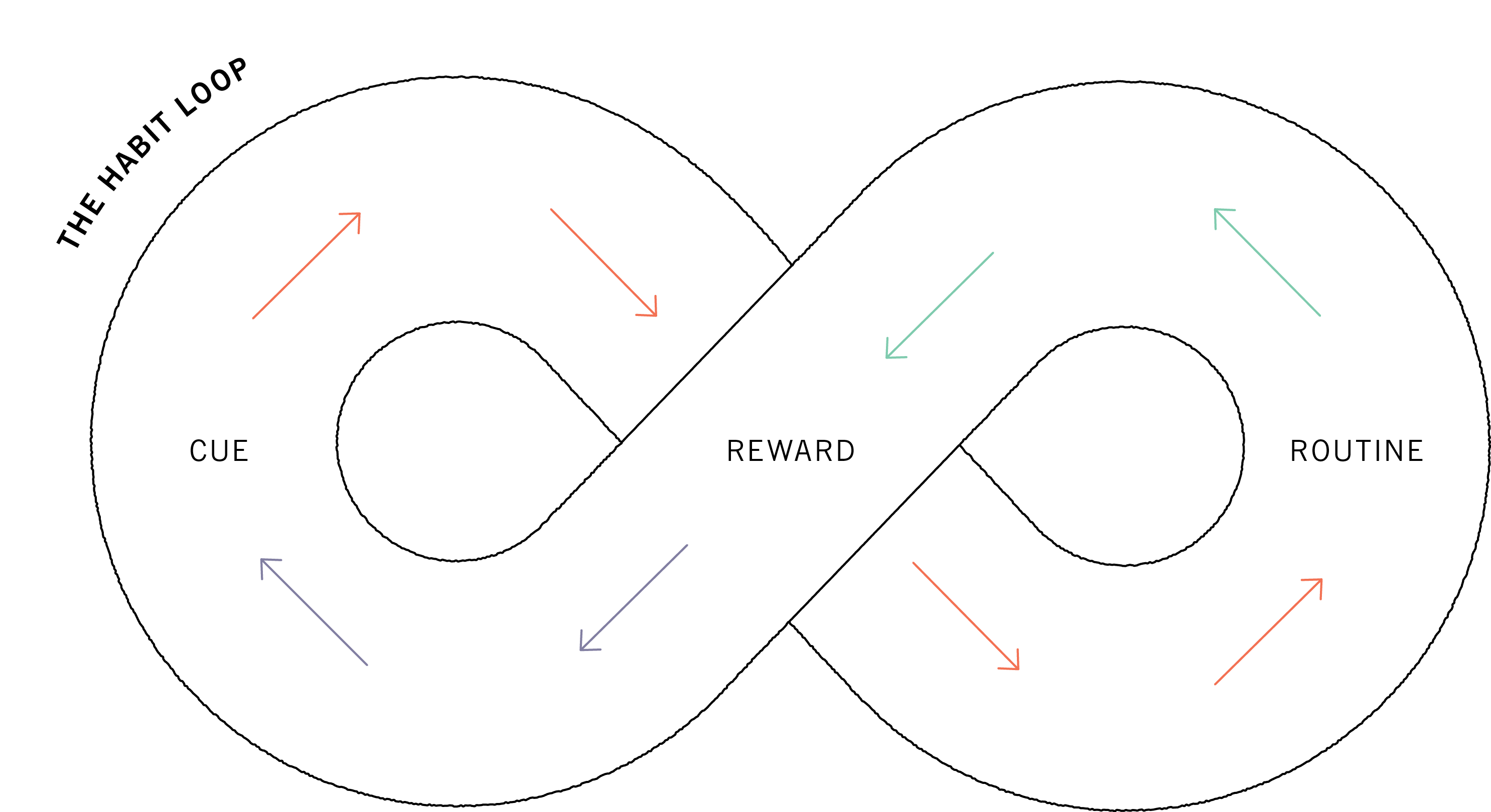

Change can be difficult because of the ingrained habits of individuals. Individuals form habits through repetition and reinforcement—routines or behaviors that regularly repeat and occur automatically. Habits can be good or bad. Without habits, we would not be able to walk and chew gum at the same time. Both of those skills have become habit for most of us, so we can do them without thinking. Research has shown that more than 40 percent of the actions we take each day are habits that do not require conscious thought or a decision.

Forming New Habits: Small Changes

Change is easiest if you start small and make bigger changes as you go along. This concept of small change is rooted in the 2,000-year-old idea put forward by the Tao Te Ching, which says, “The journey of a thousand miles begins with a single step.” It bases this philosophy in the belief that lasting change occurs through small, steady increments.

The amygdala, the primitive center portion of the brain that developed first, allows us to react quickly to outside stimuli—think “fight-or-flight.” However, even with a non-life-threatening stimulus, this primitive brain function will follow that stimulus with a habitual routine, bypassing the cognitive, thinking part of the brain. This built-in instinct is helpful when there is real physical danger, but impairs our response when the stimulus kicks off a routine that we want to change in our personal or work lives. This is why taking baby steps can be easier than tackling a large scary change at once; we avoid or minimize the fight-or-flight response.

For example, one of the authors heard his high school son bragging on one of his friends who does 100 push-ups twice a day to stay in shape. Motivated to do something physical that didn’t take long and didn’t involve a gym every day, he committed to work his way toward 100 push-ups a day.

Reinforcing Rewards: Tracking Progress Towards Goals

Another example of a small change is to create a mnemonic to help you remember the list of things you need to have with you when you leave for work every day. The cue is walking out the door. The routine is the mnemonic; the reward is arriving at work with everything you need. One of the authors created a mnemonic to help him remember to gather some things he sometimes forgot when leaving the house: his wallet (W), keys (K), ring (R), and phone (P) (WKRP, which was easy for him to remember because of a TV sitcom about a radio station with those call letters). Just going through that checklist has kept him well equipped for the workday.

Before trying to make any sort of change, it’s important to first set a goal, then remind yourself of that goal and the progress, or lack of progress, you’re making. Goals are foundational to making progress: even simply thinking through what you want helps solidify a path to change. Once you identify a goal, measuring your progress toward that these goal helps keep you on track. This constant reminder of progress helps to ensure these goals are still your priority and provides course correction when needed. If you continually lack progress against your goal, ask yourself if it’s a priority or if other aspirations are competing. Additionally, tracking progress brings to light the need to shift your behaviors going forward if you’re not accomplishing your goals.

This concept can even work for people working within an organization. We’ve seen proof of this concept at our own organization with our career-mentoring program. Leadership asked employees to make a small change by committing to meeting once a month to discuss goals and progress. This approach took an activity employees were already doing—meeting with their mentors—and made one small change: asking that the meetings happen at least once per month and cover at a minimum progress toward personal and professional goals. At the end of the month, leadership asked all career mentors to report whether the meetings took place and whether they covered personal and professional goals. Turning this behavior into a competition further drove a reward for participating. This small change led to improved career mentor relationships and noticeable improvement in the achievement of personal and professional goals in annual reviews.

When tracking progress, especially when you’re trying to form a habit, it is important to measure effort, not only results. Keeping a spreadsheet that lists your goals and a rating of the effort you made to move the ball forward against those goals can help you make progress. Rating yourself on effort keeps the goals front and center and makes you think through how hard you are really trying.

Willpower Awareness: Anticipating Weakness

To manage your willpower, prioritize your goals and tackle the hardest things when you have the most energy. No matter how good your intentions, if you’ve depleted your willpower, it’s hard to stay disciplined by the end of the day. So, if you’re a morning person, don’t spend your first hours of the day answering email. Instead, tackle your biggest challenge first.

It’s also helpful to set yourself up for success by knocking down roadblocks that might give you an excuse to skip out on your challenging task. For example, one of the authors set a goal to run four times a week. To help achieve this goal, she lays out her running clothes the night before. As simple as this sounds, it makes running first thing in the morning a routine. When the alarm goes off in the morning, she has one less excuse, picking out clothes, to get out the door. As we have all experienced, life gets in the way of working out at the end of the day. By the time you’ve gone through the daily grind, your willpower is worn down and it’s easier to skip your run.