The feature article in the Fall 2013 Jabian Journal made the case for a strengths-based approach to team management, citing empirical and theoretical evidence for a concentrated team focus on individual strengths and an outright rejection of proclivities toward diminishing weaknesses.

Evidence for strengths-based foundations is well documented in philosophical and practical writings pertaining to modern business — like Peter Drucker’s correlation of strengths with professional effectiveness or the positive psychology movement’s paralleling strengths-based focus with human fulfillment. Acknowledgement that it is good for team individuals to develop and build upon that which they do best naturally begets the next logical step — implementation.

How should a team undertake this change in focus from “fix weakness” to “develop strength?” To begin with, having individual team members singularly pursue and develop their unique strengths is likely to achieve a higher level of demonstrable success in team efficiency and performance. This simple approach to strengths development would be relatively unobtrusive to daily team dynamics. Leaving individuals free to use their strengths to realize strategic outcomes may help them become more productive, but the results may be less than satisfying. Why? Because they rarely do it, and when they do, it is rarely done correctly. Consider the following study.

Gallup recently asked more than 11,000 employees to what extent they agreed with the following statement: “Every week, I set goals and expectations based on my strengths.” Only 36 percent strongly agreed. What’s more, extensive research on 360-degree feedback instruments confirms that, as a rule, individuals are not precise about what they perceive to be their strengths and weaknesses, as their self-assessment scores tend to be notably deviant from everyone else’s. Such data suggests the need for alternatives. As such, many of the world’s best managers have begun to invest their time learning the strengths of their individual team members and managing their team with those strengths in mind. This type of strengths-based environment requires a fundamental shift in both team management and execution, as well as the idea that such a shift must be rooted in an organizational culture that champions and cultivates both.

Step One: Pinpoint Individual Strengths to Develop

Leaders of teams must look beyond first impressions when identifying the potential strengths of individual team members. Though they often are fairly accurate — a notable and helpful truth — they’re not comprehensive. A complete view is important when assessing individual competencies for high-impact strengths or potential fatal flaws — a weakness at or below the bottom 10 percent compared to others.

It is not fundamentally wrong to place some value on initial assessments of individuals based on first impressions and informal contact. However, thorough and comprehensive analysis should always be considered if the impacted parties are expected to authentically pursue action plans based on such.

Before we look at the core competencies most associated with high-achieving individuals, it is important to note that any fatal flaw revealed by an individual strengths assessment must be addressed immediately. These types of weaknesses (which are considered profoundly weak, imperative to the job at hand, and readily observable to others) eclipse and essentially nullify the impact of any individual’s profound strengths. Thus, it is imperative that an individual first correct the obvious flaw in order to proceed from negative territory to “ground zero.” Once that has been achieved, the focus can then be shifted to the “positive deviance” side of the equation, where building distinguishable strengths can be explored.

After examining assessments from 200,000 respondents, Jack Zenger, Joseph Folkman, and their team identified 16 core competencies that best distinguish the most effectual individual contributors from the rest. They condensed them into five competency areas:

Character

The individual sustains high levels of honesty and integrity.

Personal Capability

In addition to technical and professional expertise, the individual is able to analyze and solve problems, innovate, and self-develop.

Results Focused

The individual is able to push past the notion of “good intentions” and drive toward final outcomes, including stretch goals and identification of future initiatives.

Interpersonal Skills

The individual is able to communicate with powerful clarity, while simultaneously building relationships and developing others along the way.

Leading Change

The individual has robust perspective, champions authentic change, and connects the team to mindsets that exist outside the group.

Assessing individual team members’ competencies in these areas is the first step toward building an environment geared toward a heightened awareness of individual assets. These competencies provide insight into individuals’ thought patterns regarding how they communicate, what motivates them, how they establish direction and make decisions, how they surmount obstacles, how they build and sustain relationships, and, perhaps most importantly, how they want their achievements celebrated.

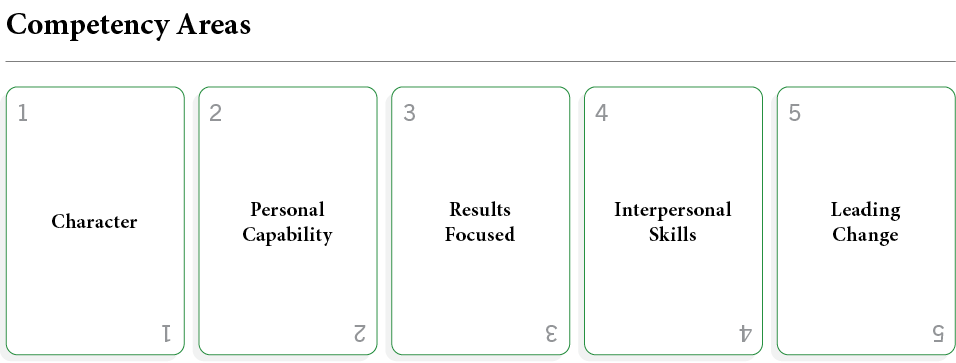

Moreover, research has found that managers who can focus on an individual’s competencies can directly affect that individual’s level of engagement. In his book, “StrengthsFinder 2.0,” Tom Rath documents Gallup’s 2004 research on what happens when a manager focuses on an individual’s strengths, focuses on an individual’s weaknesses, or simply ignores that individual. Gallup found that 55 percent of individuals who felt their managers honed in on their weaknesses were not engaged or were even actively disengaged.

However, Gallup also found that when managers focused on an individual’s strengths, the chance of that individual being actively disengaged was reduced to one in 100. Plainly stated, when individuals are convinced that their bosses and their organizations are interested in leveraging and developing the things they love to do (and do well), they will more enthusiastically embrace their work and engage with those around them.

In addition to acknowledging individuals’ strong competencies and gleaning what strengths they are most passionate about developing, there remains a final component to pinpointing strengths — that of organizational need. In order for individual contributors to be successful in a team environment, their competency areas (and passion for them) must also be organizationally aligned. Just as there is that singular point on a bat, racket, or club at which it makes the most effective contact with the ball, there is an optimum point where competence and passion intersect with organizational needs to create an achievement “sweet spot” for both the individual and the organization. Knowledge of where these three factors overlap helps individuals determine which strengths should be targeted for development. Naturally, leaders of teams should focus on those strengths informally and within professional development plans.

Step Two:Return to Basics

Once an individual’s strengths development plan has been finalized, that individual should initially employ a traditional linear approach to strengths augmentation — that which is a logical, obvious approach to improvement. This type of advancement involves a return to simplicity and an adherence to the fundamental principle that most skills are learned by watching others. Because this stage requires individuals to look at their strengths from the most basic of levels, personal observation serves as the starting point for building strengths. Essentially, this type of development entails individuals watching others perform the skills they are intent on acquiring and then selecting, for personal employment, those actions they feel can be feasibly and comfortably duplicated.

Learning in this manner — by watching how company leaders conduct meetings, ask questions, respond to others, delegate tasks, and develop processes or service offerings — allows individuals

to deliberately build on their strengths in the course of normal daily work. Though this course of action occurs informally and is seldom scripted, it is actually foundational to the development of strategic perspective within the proper context. This type of framework allows the information to resonate with insight in a way that is relative and valuable to the individual, the team and the organization.

Most organizations couple personal observation with some type of formal development (both individual and process skill), coaching (both formal and informal), and deliberative practice. When combined, this back-to-basics approach is highly proficient and adaptable for the individuals who want to build a particular strength. Strengths-based researchers would acknowledge these activities (books, classes, journals, observation, etc.) have strong “face validity” – in that these types of plans appear effective in terms of their stated aims. These pursuits are systematic, scientific-method-like approaches to strength augmentation. And they will work for managers seeking to develop teams of high achieving individuals — to an extent.

Because this type of development is linear, the individual’s growth is static. The individual will eventually realize the effort he is putting forth is out of proportion with the pace of his development. In other words, singularly pursuing an isolated strength (through personal observation, books, journals, coaching, etc.), though initially valuable, will always —

always — reach a point of diminishing returns when the individual achieves a higher level of proficiency. That is where the concept of cross-training comes into play.

Step Three:Cross-Train Across Competencies

Most people undertake cross-training for a specific reason. Aspiring runners often cycle and swim; swimmers will strength train; many golfers practice yoga. Why? Runners could say there is a strong statistical correlation between skilled cyclists and those who excel at running. Swimmers may tell you that strength training helps build their stroke. Many golfers could affirm that yoga is essential for boosting the mental stamina of their game. But the most rudimentary reason for such pursuits is that engaging in one has been shown to help people perform the other more successfully.

In the realm of strengths augmentation, Zenger and Folkman consider cross-training to mean the discovery of how certain leadership competencies are interlaced with one another. This type of nonlinear approach is centered on the idea that profound strengths are created when certain core competencies are intermingled in such ways that the blending of those skills creates an effect that is greater than the sum of the effect of each skill individually.

While data mining huge data sets of 360-degree assessments, the Zenger and Folkman team found that each differentiating competency was statistically linked to a sprinkling of other behaviors. This simple finding opened up an entire flow of research that allowed them to identify between five and 12 companion behaviors (some that were intuitively obvious and others that were “jarringly nonintuitive”) for each of the differentiating competencies. For instance, the Zenger and Folkman team found the companion behaviors that most correlated with “practices self-development” were: listens; is open to others’ ideas; shows respect for others; displays integrity; avoids taking credit for others’ successes; desires to develop others; takes initiative; and is willing to take risks and to challenge the status quo. The correlation of these companion behaviors with “practices self-development” were, at first glance, not understood in an instinctive, subconscious way in that they are all neither self-focused nor even inwardly focused. And yet the empirical data led the researchers to realize that practicing self-development has more to do with how individuals interact with others than how many journals they read, training sessions they attend, or personal goals they set. The difficulty with most development action plans is that, though they pinpoint what individuals should improve and build on, they often are inadequate frameworks for telling individuals how to go about it. This is where targeting companion competencies can make a significant difference: by providing connections between the core competency being developed and other specific, correlated behaviors.

For individuals who have exhausted linear outlets or are already quite skilled at some proficiency, these competency companions afford a fresh, more complete avenue to developing a strength. These companions allow high-achieving individuals to essentially create new areas for growth by blurring the boundaries of individual competencies and thinking across them. For example, Zenger and Folkman found it is irrelevant to focus on questions such as whether individuals with either strong technical expertise or strong professional expertise make better leaders. Instead, their research would assert that a better leader would arise in an individual with deep technical or professional expertise and who also is able to convey that expertise to others in a tangible way. Expertise (technical or professional) without powerful communication skills renders less valuable the inherent strength of either proficiency. It is the combining

of both skills that produces the greatest effect.

Though research has yet to pinpoint the exact reasons for the correlation between companion behaviors and differentiating competencies, it nevertheless demonstrates that individuals who score high on one also tend to score high on the other. Conversely, individuals receiving low scores on a differentiating competency also receive low scores on associated companion behaviors — as if they were bound together. Therefore, it makes sense that raising the score on one will likely also raise the score of the other. Cross-training eliminates the distortion that linear thinking often introduces because individuals must focus on strengths as an integrated whole, rather than artificially breaking them into horizontal compartments that have little or nothing to do with one another. It is from this integration of core competencies and companion behaviors that profound strengths emerge.

Augmenting a strength through cross-training invariably demands greater involvement and commitment on the part of the individual than fixing a weakness or learning a new strength linearly. But making the transition from “good” to “great” is more intensive because the level of skill needs to be distinctively better. And because non-linear development plans tend to require elevated and sustained levels of dedication, concentration, and pure hard work, managers of teams must build in avenues for extensive feedback into the overall strengths development experience.

Step Four:Build In Feedback Processes

Simply put, built-in feedback processes augment the value of linear and non-linear development plans because they provide a clearer picture of an individual’s competency level for both that individual and the individual’s manager. Seeking and accepting feedback is a fundamental skill for every individual, and yet assessments show that established leaders (executives and senior managers, in particular) are not inclined to ask for feedback from anyone at any level — not their superiors, peers, or their subordinates. But asking for feedback is essential for managers of teams because it sets the tone for team dynamics. If managers respond well to honest, constructive feedback, chances are the individuals on the team will, too. Moreover, Zenger and Folkman found an excellent correlation between the willingness of leaders to request feedback from others and overall leadership effectiveness. Specifically, when leaders were evaluated by their employees, those who scored in the bottom 10 percent in the “willingness to ask for feedback” category only scored in the 17th percentile in terms of “overall leadership effectiveness.” Conversely, leaders who ranked in the top 10 percent in “willingness to ask for feedback” also ranked in the 83rd percentile in “overall leadership effectiveness.” Perhaps this is because the single best way to accurately assess how well a person manages teams is through the discernment of those being managed.

When implementing strengths-based team management, feedback mechanisms are integral because the entire team is in need of collective, actionable assessments of their skills in specific core competency areas. These assessments are both sweeping and yet granular, and they demonstrate to individuals what the team and organization value the most. Seeking the opinions of others and welcoming those opinions conveys respect, reduces barriers between management levels, and provides the team with valuable information that cannot be obtained any other way. Teams are comprised of people — not processes. They are the product of human interaction and social construction, and collaborative, innovative, and strengths-based processes emerge only when people engage in dialogue — and appreciatively so.

Zenger and Folkman assert that one of the reasons that people all over the globe enjoy partaking in competitive games and sports is because they provide immediate feedback. Children receive immediate gratification when they score a goal, serve an ace, or beat their opponent to the finish line. As such, this type of instant feedback allows children to know in real time if what they are doing is working or requires adjustment. From this type of feedback often stems great joy and continued dedication. And it is this that strengths-based teams should aspire to, with the ultimate goal of becoming a feedback-rich environment, where there is an outpouring of information that is both recognized and realized.

Step Five:Create Sustainability

In the book, Practicing Organization Development:

A Guide for Consultants, Jane Magruder Watkins and Jacqueline Stavros discuss the idea of a positive core — the heart of an organization at its best. Within this core is the idea that every person has a unique set of strengths to offer, and when organizations choose to focus on those strengths, the organizational shift is not so much about the methods of the strengths development process itself, but rather the reallocation of organizational perspective toward the highest aspirations and best practices. And that is why the final step in the implementation of strengths-based team management is enduring and consistent organizational support. Zenger and Folkman believe that organizations are achieving strengths-based sustainability if they are able to affirmatively answer the following questions:

- Have we created a corporate environment that is supportive (at all levels) of strengths-based development?

- Have we provided our employees with clearly defined outcomes for the development?

- Have we established well-defined, long-term accountability processes to ensure our employees can implement and apply their strengths effectively?

- Have we built visibility and credibility into our organization in such a way that we are able to tout the accomplishments of our employees and reward them accordingly?

- Do we have in place purposeful methods of follow-up, with an eye toward constructing the best and highest future for our organization’s human capital management?

Infusing the strengths philosophy into all organizational areas begets sustainability because it requires all components of the organizational environment — managers, peers, subordinates, and human resources — to work together to support strengths-based management of teams. A strengths-based environment connects everyone in such a way that there is no such thing as an objective observer; everyone has a role. This is because strengths-based sustainability is predicated on the understanding that strong team members volunteer their strengths to the team most of the time. Teams that operate in this way evolve to become intimately aware of the diversity of strengths within the team, thereby allowing for sophisticated approaches to project and task execution. For critical work scenarios, team members play to their strengths in order to optimize results, further their development and maximize individual fulfillment. During less critical times, the team has the ability to modify roles and responsibilities to enable the pursuit of companion competencies. Clearly, these types of opportunities simultaneously create more options for optimal execution in the long term.

Throughout his career, Peter Drucker often expounded on the idea that effective leaders know how to make their teams productive because they understand that leveraging individual team member strengths is the unique purpose of the organization itself. He believed that when teams are composed of people whose strengths are identified, understood, and integrated, the team as a whole is more engaged, more loyal, and more productive. Effective managers of teams are drivers of those attributes because they acutely understand the nuances of team member strengths and position them accordingly.

Many organizations look for optimal solutions to poor levels of engagement, satisfaction, and commitment. They explore everything from elevated pay and first-rate healthcare to child care and work-life balance. But in all of Zenger and Folkman’s research about what makes an employee satisfied, engaged, and committed versus one who is dissatisfied, disengaged, and uncommitted, one variable emerged as the superlative forecaster of the difference: who managed that employee. And that is the variable most deserving of an organization’s attention.

The leap from well-rounded individuals to uniquely strong teams is not for the faint-hearted. It is a fairly complex, occasionally uneven road, toward the building of sustainable, positive organizational momentum. The effectiveness of the manager is the absolute precursor for everything else. Successful managers know that the use of all available individual strengths is the most genuine opportunity for joint achievement. It is that knowledge that renders worthy the strengths-based journey.