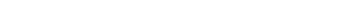

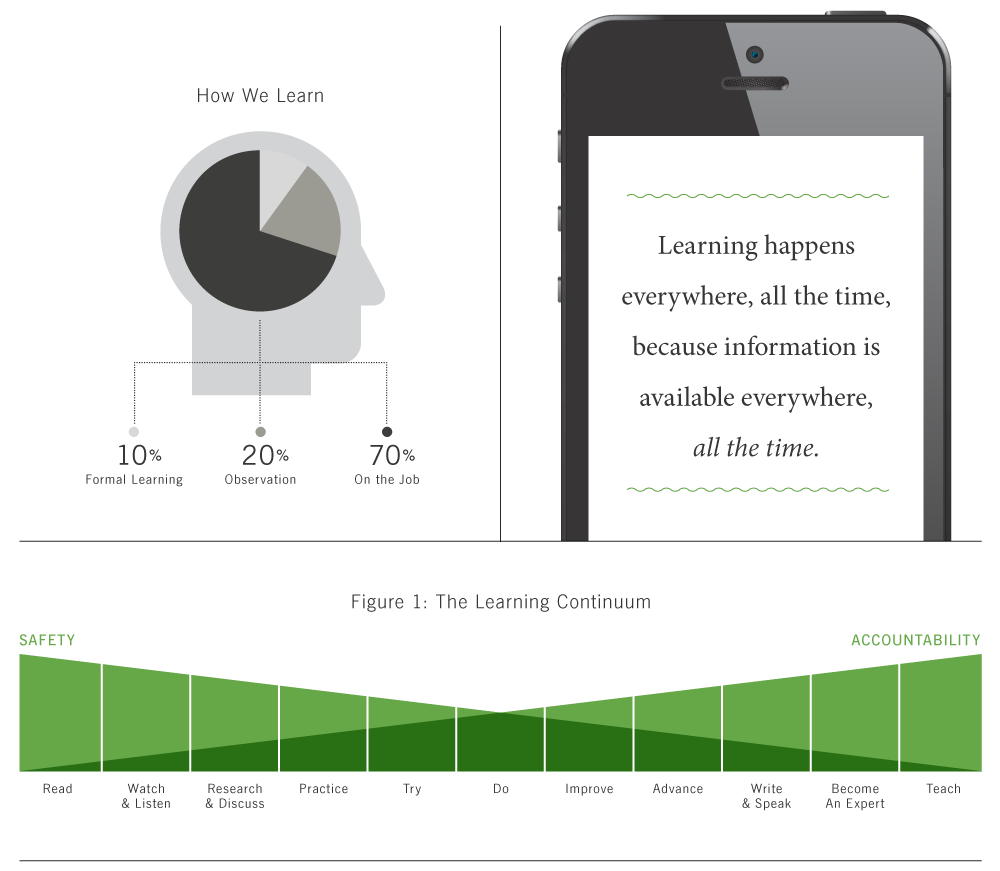

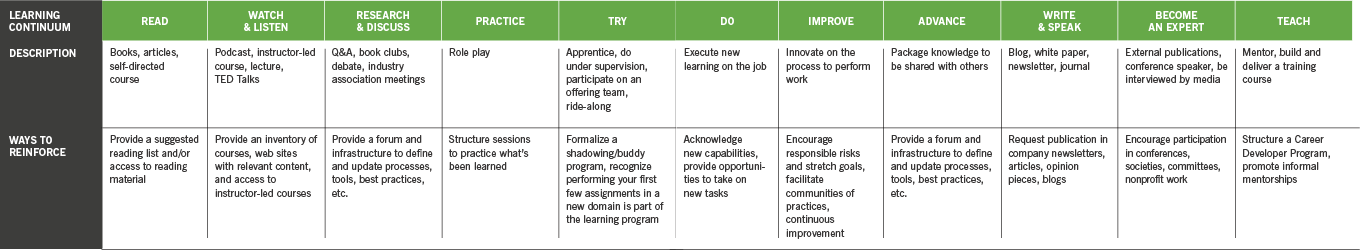

We have developed a framework organizations can use to help their people think through their progression towards mastery in a given domain. Figure 1 shows a continuum of learning, based on the activities people do while learning: from reading, listening, watching, and discussing, through doing, advancing the craft, and eventually giving back. Indeed, only the far left side of the continuum involves formal learning. Lombardo and Eichenger presented research in the 1970s demonstrating that only a very small part of learning, about 10 percent, comes from formal learning (e.g., classroom training and reading), while about 20 percent comes from observation and watching others perform the task. Meanwhile, the vast majority of learning — about 70 percent — comes from “on-the-job” experiences. Most of the activities found in the continuum are at least experiential, if not “on-the-job” activities.

By considering the breadth of the activities in the framework, learning is not constrained by the development capacity or budget of the learning and development group. Google, for example, introduced “G2G” (Googler to Googler), an employee-to-employee learning program allowing individuals to shadow, practice, or otherwise learn from their colleagues. The program shifted the focus away from instructor-led training, reducing the bottleneck of formal training development, thereby keeping up with employee learning demands.

Organizations can open their employees’ eyes to the many ways they can take ownership of their own progression toward mastering their craft by communicating and deploying our framework to its workforce.

The methods on the left side of the continuum are relatively safe. You have little or no “skin in the game” when you’re reading a book, listening to a podcast, or learning from a video online. We start toward the left side of the continuum when we’re learning something new. We may not always start at the far left, as we’ve all had the experience of attempting “some-assembly-required” projects — without the manual. However, when we get stuck, we’ll usually slide back to something more basic to pick up what we couldn’t figure out by trial-and-error. As you move toward mastery, risk increases. You might make mistakes. You might even fail, but you’ll be learning. As you advance along the continuum, others begin to count on you to deliver, and employers begin to compensate you for what you are doing for them. Eventually, you may progress to advancing the domain you’re operating in, by inventing a new way of doing things, for example. That involves significant accountability and risk, but it also drives innovation and progress.

While you can use extrinsic motivation to require someone to attend a course or take a test, people have to be intrinsically motivated to progress through the entire continuum, from learning to mastery. Moving to the right side of the continuum requires a voluntary and a proactive kind of learning, which is critical to the growth and career development of engaged employees. The focus is less on immediate needs and more on building on experience for the future. Because intrinsic motivation for this kind of learning is so important, learning and development groups should focus on teaching people how to achieve mastery (i.e., by sharing this framework), then putting structures in place to help people advance along the continuum (see diagram above).

Taking a broad view of learning is difficult to track, manage, and measure, but this should not stop us from creating a culture that reinforces mastery. Leaders must watch for progress along the continuum and reinforce it when it happens. Incorporating the continuum into a self-assessment and the performance management process is a great way to reinforce, recognize, and drive progress. Leaders should ask questions like, “What have you done to move toward mastery? What’s slowing you down? What can we, as leaders, do to help you?”

Of course, it’s rare when someone moves all the way to true mastery in many domains. Specific jobs often require technical expertise, and employees can achieve that technical expertise once they’ve become competent at the “Do” and “Improve” stages of the model. Sometimes that’s enough. But mastery begins to take shape as employees move away from learning because their job requires it (extrinsic motivation) to learning for themselves (intrinsic motivation).

Organizations that provide a broad view of learning and development — incorporating the breadth of information and learning mediums while steering their workforce towards a mindset of mastery — can improve both how much people learn and their level of engagement. That’s good for everyone: customers, shareholders, suppliers, and employees.